A History of St George's, Headstone

Historic Headstone

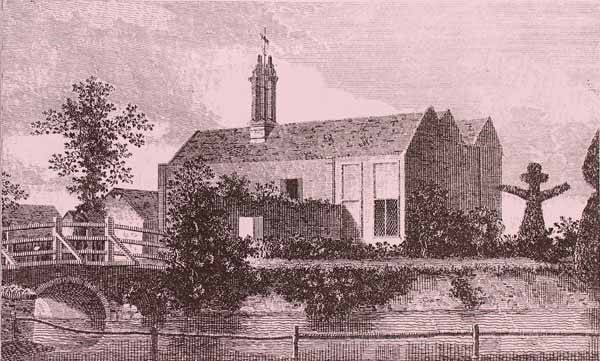

Engraving of Headstone Manor by James Pellar Malcolm, 1800

Engraving of Headstone Manor by James Pellar Malcolm, 1800

The Church’s association with Headstone goes back at least as far as 825 when the land, as part of Herga, came into ecclesiastical ownership under Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury. Headstone first appears in records as a distinct area in 1233. The name, probably deriving from two Saxon words meaning ‘enclosed homestead’, has been found with over twenty spellings including Hegton, Hegeton, Heggeston and Hedgstone.

In 1344 Archbishop of Canterbury John Stratford, the feudal overlord, purchased the Headstone estate centred on its moated grange, and the early 14th century house became the archbishops' chief residence in Middlesex. Cardinal Archbishop Simon Langham conducted ordinations in the chapel at the manor in June 1367; Lambeth estate records indicate that the chapel may have been removed during rebuilding in 1488/89. On 20th July 1407 Archbishop Thomas Arundel, engaged in combating the early stages of the Lollard movement, wrote to Nicholas Bubbewyth, Bishop of London, from his manor at Headstone. With a view to alleviating tensions between Church and State he proposed a series of solemn processions with a grant of forty days’ indulgence to those taking part. The Reformation, which swept away indulgences, also saw Archbishop Thomas Cranmer ‘invited’ by Henry VIII to exchange Headstone Manor for land elsewhere. It was surrendered to the king in December 1545 and within days passed from the Crown into private ownership.

Headstone remained an agricultural estate until the 20th century. In the late nineteenth century it became known for its rowdy horse races. In her History of Pinner Patricia Clarke writes that ‘the Headstone Races – farmers’ races – took place in a field at Headstone, north of Southfield Park, but after a few years they were abolished following riots, thieving and assaults – of which the gentlest was throwing someone into the moat – perpetrated by marauders from London in 1899, or so it was alleged’.

In 1344 Archbishop of Canterbury John Stratford, the feudal overlord, purchased the Headstone estate centred on its moated grange, and the early 14th century house became the archbishops' chief residence in Middlesex. Cardinal Archbishop Simon Langham conducted ordinations in the chapel at the manor in June 1367; Lambeth estate records indicate that the chapel may have been removed during rebuilding in 1488/89. On 20th July 1407 Archbishop Thomas Arundel, engaged in combating the early stages of the Lollard movement, wrote to Nicholas Bubbewyth, Bishop of London, from his manor at Headstone. With a view to alleviating tensions between Church and State he proposed a series of solemn processions with a grant of forty days’ indulgence to those taking part. The Reformation, which swept away indulgences, also saw Archbishop Thomas Cranmer ‘invited’ by Henry VIII to exchange Headstone Manor for land elsewhere. It was surrendered to the king in December 1545 and within days passed from the Crown into private ownership.

Headstone remained an agricultural estate until the 20th century. In the late nineteenth century it became known for its rowdy horse races. In her History of Pinner Patricia Clarke writes that ‘the Headstone Races – farmers’ races – took place in a field at Headstone, north of Southfield Park, but after a few years they were abolished following riots, thieving and assaults – of which the gentlest was throwing someone into the moat – perpetrated by marauders from London in 1899, or so it was alleged’.

Mission District

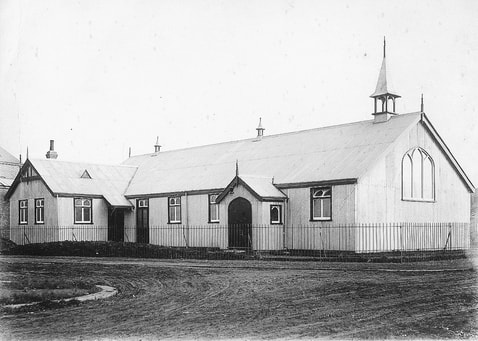

Temporary church, 1907

Temporary church, 1907

On 13th December 1906 a meeting of the Council of the London Diocesan Home Mission received an application for the establishment of a mission district from the Rev. Frank Bealey, Vicar of Hatch End. A member of the Council present at the meeting was the Rev. J. H. Cardwell, Rector of St. Anne’s, Soho, where Bealey was a curate from 1900-1902 and where the soon-to-be appointed Missioner of the new district – Ramsay Couper – had been serving as a curate since 1899. Nowhere in surviving L.D.H.M. records is there an explanation for the dedication of the new ecclesial entity to St. George; it is merely stated, in a volume detailing the progress of St. George’s, that ‘this District was formed in the period July-December 1906’. The mission district lay wholly within the parishes of St. Anselm’s, Hatch End (436.6 acres) and St. John’s, Greenhill (101.4 acres).

Frank Bealey became the first Vicar of St. Anselm’s, Hatch End on 27th October 1906, having previously been a curate of the Rev. Charles Grenside, Vicar of Pinner Parish within which St. Anselm’s was a chapel-of-ease. E. M. Ware, in his Pinner in the Vale, tells of the background to this appointment: ‘Mr. Grenside while on holiday in Italy was embarrassed to find he had insufficient current money to pay for his meal. A stranger came to his aid, it was Mr. Bealey, and this started a life-long friendship.’

The Pinner and Hatch End Magazine of June 1907 drew attention to the worshipping needs of people in the new residential area rapidly springing up to the south-west of the Kodak works:

Ever since this quarter began to grow, the problem has been to provide for the spiritual needs of its residents. Where were they to go to Church? Their original parish church, that of Pinner, was too far away, and their present parish Church of St. Anselm’s is farther away still, whilst in bad weather the roads – well, any one who has tried to negotiate Headstone Lane on a bicycle during the winter months will remember what he said to the crows!

In 1910 the Rev. Ramsay Couper recalled his introduction to Headstone:

I well remember the occasion on which I first heard of the place. My old friend and former colleague, the Rev. F. A. J. Bealey, called on me at 28, Soho Square, told me about the proposed District and said that he wished me to become its Missioner. I was naturally interested, and felt that the first thing to do was to go and see the place.

My earliest impressions of Headstone were not very favourable. I paid it my first visit on Boxing Day, 1906. There had been a heavy snowstorm during the previous night, and the snow was so deep that it was impossible to see where roads ended and fields began. Not a soul was visible, and the place looked dreary in the extreme. The snow, however, gave one the idea that both roads and fields were possessed of a beautiful evenness of surface, an impression as regards the former that was destined to be quickly shattered by a closer acquaintance.

Further visits, however, dispelled the unfavourable impression, and to make a long story short, I was appointed Missioner by the Bishop of London, and took up residence on Monday 27th May, 1907.

To find myself in a neighbourhood that was entirely strange, among people of whom I did not know a soul, and without any Church or place to hold services was a novel experience. The first thing was undoubtedly to get to know everybody in the district. Accordingly I spent weeks in house to house visiting, meeting with all kinds of receptions, but gradually interesting an increasing number in the new undertaking.

Born in 1865, Ramsay Wyatt Couper was the son of Ramsay Hamilton Couper, ‘Gentleman’, and the grandson of Colonel Sir George Couper, created 1st Baronet Couper in 1841. Ramsay Couper was educated at Reading School and read theology at Keble College, Oxford. He was ordained deacon in 1899 and priest the following year.

A meeting publicly launching the new venture of St. George’s was held in the Cricket Pavilion on the Harrow Recreation Ground on 9th July 1907 and attended by 75 people. The Rev. Frank Bealey spoke, sketching the progress so far and introducing Ramsay Couper. Frank Bealey reported that the Bishop of London’s Fund had bought a site for a church in Pinner View and was making a grant available towards the cost of building a temporary church. The meeting offered the Rev. Ramsay Couper ‘a real hearty welcome’ and a pledge of support. A Building Committee for a temporary church was formed with Bealey as Chairman; among the members was Mr. Charles Landon of ‘Pengwern’, Cunningham Park, who became honorary architect.

The temporary church – a corrugated iron structure capable of seating 300 – was dedicated by the Rt. Rev. Charles Turner, Bishop of Islington, on 25th October 1907. It was built at a cost of £850, £350 having been granted by the Bishop of London’s Fund. Thanks to the fundraising efforts of the congregation, including proceeds from the first Bazaar, opened on 2nd June 1908 by Lady Edward Spencer-Churchill, the building was paid for within less than eight months.

A 1911 report of the Bishop of London’s Fund offers a glimpse of St. George’s in the days of the temporary church:

It must be confessed that, after the interest created by the Dedication had subsided, the congregations in the early days of the temporary Church were very disappointing. The state of the roads leading to the Church accounted for much; lamps were non-existent; the building itself could hardly be called an attractive place of worship, being very cold in winter and very hot in summer. Only the really keen ones came. But after a time, things to a certain extent righted themselves. With the rapid growth of population the tide turned. The congregation gradually increased, until on Sunday evenings the Church was uncomfortably crowded.

Adverse conditions around the temporary church were described in the St. George’s Magazine of November 1907 in an article entitled ‘St. George’s in the Mud’:

This product of some facetious mind has been suggested as an appropriate name for our new Church. We cannot help being amused at our new title, but unfortunately the condition of the roads leading to St. George’s is far too serious to be treated as a joke.

The pools of water, the quagmires, the deep ruts and holes, the kerb stone at one time level and at another lying at an angle of 45 degrees, the numerous obstacles on the paths and roads – all these are bad enough when daylight enables us to pick our steps; but when darkness covers the whole, they are positively dangerous. One gentleman who was endeavouring to come to church fell over some obstacle, and was so shaken that he had to return home; another wandered about in the mud and darkness, but never found the Church; some ladies were seen at the corner of Cunningham Park and Harrow View, striking matches to help them in finding their way through ‘this dreadful place’, as they rightly called it.

Frank Bealey became the first Vicar of St. Anselm’s, Hatch End on 27th October 1906, having previously been a curate of the Rev. Charles Grenside, Vicar of Pinner Parish within which St. Anselm’s was a chapel-of-ease. E. M. Ware, in his Pinner in the Vale, tells of the background to this appointment: ‘Mr. Grenside while on holiday in Italy was embarrassed to find he had insufficient current money to pay for his meal. A stranger came to his aid, it was Mr. Bealey, and this started a life-long friendship.’

The Pinner and Hatch End Magazine of June 1907 drew attention to the worshipping needs of people in the new residential area rapidly springing up to the south-west of the Kodak works:

Ever since this quarter began to grow, the problem has been to provide for the spiritual needs of its residents. Where were they to go to Church? Their original parish church, that of Pinner, was too far away, and their present parish Church of St. Anselm’s is farther away still, whilst in bad weather the roads – well, any one who has tried to negotiate Headstone Lane on a bicycle during the winter months will remember what he said to the crows!

In 1910 the Rev. Ramsay Couper recalled his introduction to Headstone:

I well remember the occasion on which I first heard of the place. My old friend and former colleague, the Rev. F. A. J. Bealey, called on me at 28, Soho Square, told me about the proposed District and said that he wished me to become its Missioner. I was naturally interested, and felt that the first thing to do was to go and see the place.

My earliest impressions of Headstone were not very favourable. I paid it my first visit on Boxing Day, 1906. There had been a heavy snowstorm during the previous night, and the snow was so deep that it was impossible to see where roads ended and fields began. Not a soul was visible, and the place looked dreary in the extreme. The snow, however, gave one the idea that both roads and fields were possessed of a beautiful evenness of surface, an impression as regards the former that was destined to be quickly shattered by a closer acquaintance.

Further visits, however, dispelled the unfavourable impression, and to make a long story short, I was appointed Missioner by the Bishop of London, and took up residence on Monday 27th May, 1907.

To find myself in a neighbourhood that was entirely strange, among people of whom I did not know a soul, and without any Church or place to hold services was a novel experience. The first thing was undoubtedly to get to know everybody in the district. Accordingly I spent weeks in house to house visiting, meeting with all kinds of receptions, but gradually interesting an increasing number in the new undertaking.

Born in 1865, Ramsay Wyatt Couper was the son of Ramsay Hamilton Couper, ‘Gentleman’, and the grandson of Colonel Sir George Couper, created 1st Baronet Couper in 1841. Ramsay Couper was educated at Reading School and read theology at Keble College, Oxford. He was ordained deacon in 1899 and priest the following year.

A meeting publicly launching the new venture of St. George’s was held in the Cricket Pavilion on the Harrow Recreation Ground on 9th July 1907 and attended by 75 people. The Rev. Frank Bealey spoke, sketching the progress so far and introducing Ramsay Couper. Frank Bealey reported that the Bishop of London’s Fund had bought a site for a church in Pinner View and was making a grant available towards the cost of building a temporary church. The meeting offered the Rev. Ramsay Couper ‘a real hearty welcome’ and a pledge of support. A Building Committee for a temporary church was formed with Bealey as Chairman; among the members was Mr. Charles Landon of ‘Pengwern’, Cunningham Park, who became honorary architect.

The temporary church – a corrugated iron structure capable of seating 300 – was dedicated by the Rt. Rev. Charles Turner, Bishop of Islington, on 25th October 1907. It was built at a cost of £850, £350 having been granted by the Bishop of London’s Fund. Thanks to the fundraising efforts of the congregation, including proceeds from the first Bazaar, opened on 2nd June 1908 by Lady Edward Spencer-Churchill, the building was paid for within less than eight months.

A 1911 report of the Bishop of London’s Fund offers a glimpse of St. George’s in the days of the temporary church:

It must be confessed that, after the interest created by the Dedication had subsided, the congregations in the early days of the temporary Church were very disappointing. The state of the roads leading to the Church accounted for much; lamps were non-existent; the building itself could hardly be called an attractive place of worship, being very cold in winter and very hot in summer. Only the really keen ones came. But after a time, things to a certain extent righted themselves. With the rapid growth of population the tide turned. The congregation gradually increased, until on Sunday evenings the Church was uncomfortably crowded.

Adverse conditions around the temporary church were described in the St. George’s Magazine of November 1907 in an article entitled ‘St. George’s in the Mud’:

This product of some facetious mind has been suggested as an appropriate name for our new Church. We cannot help being amused at our new title, but unfortunately the condition of the roads leading to St. George’s is far too serious to be treated as a joke.

The pools of water, the quagmires, the deep ruts and holes, the kerb stone at one time level and at another lying at an angle of 45 degrees, the numerous obstacles on the paths and roads – all these are bad enough when daylight enables us to pick our steps; but when darkness covers the whole, they are positively dangerous. One gentleman who was endeavouring to come to church fell over some obstacle, and was so shaken that he had to return home; another wandered about in the mud and darkness, but never found the Church; some ladies were seen at the corner of Cunningham Park and Harrow View, striking matches to help them in finding their way through ‘this dreadful place’, as they rightly called it.

Vicar, churchwardens, sidesmen, verger and choir, c1908

Vicar, churchwardens, sidesmen, verger and choir, c1908

Surely the authorities can at least see their way to give us lamps in Harrow View and Cunningham Park, and to make the paths fit for the use of pedestrians. It is really pitiable to see our people at church-time wandering about these miserable roads, and we are not in the least surprised at the strong and widespread feeling which the matter is causing in the district.

Applying for church grants in 1909 and 1910 Ramsay Couper described the people of the district as ‘mostly clerks and artizans’ and ‘lower middle class with a large mixture of the working class’. In his A Journey Just Begun, Jim Stewart observes that ‘early editions of the St. George’s Magazine were filled with details of how much this or that person had donated towards one thing or another’, and comments that ‘it would be very difficult for anyone to come regularly to such a church if they were unable to indulge in conspicuous giving’. Yet even as public amenities improved and the upwardly-mobile progressed, the great majority of members of St. George’s remained, like most people of the parish, moderately prosperous, not well-to-do.

Applying for church grants in 1909 and 1910 Ramsay Couper described the people of the district as ‘mostly clerks and artizans’ and ‘lower middle class with a large mixture of the working class’. In his A Journey Just Begun, Jim Stewart observes that ‘early editions of the St. George’s Magazine were filled with details of how much this or that person had donated towards one thing or another’, and comments that ‘it would be very difficult for anyone to come regularly to such a church if they were unable to indulge in conspicuous giving’. Yet even as public amenities improved and the upwardly-mobile progressed, the great majority of members of St. George’s remained, like most people of the parish, moderately prosperous, not well-to-do.

Parish Church

Interior, c1911

Interior, c1911

The architect for the new church was formally appointed in December 1909. The St. George’s Magazine related how the choice came to be made:

When this important question was under consideration, a small committee was appointed to inspect new churches in various parts of greater London. After visiting many buildings of different types the committee discovered a really fine church in the neighbourhood of Tottenham. They asked the Verger the name of the architect, and he told them it was Mr. J. S. Alder. Further specimens of his work confirmed the favourable impression, and Mr. Alder was appointed. Thus it was not by recommendation, but by merit alone that Mr. Alder was chosen, and we need hardly say we have every reason to congratulate ourselves on the choice.

John Samuel Alder (1847-1919) gained a reputation for combining sound building with economy to produce elegant, uncluttered churches. His work – Arts & Crafts-informed Gothic Revival, distinguished by a masterly handling of light and space – was much in demand at the end of the great period of suburban church building before the First World War. Most of his commissions came from within the Diocese of London.

In the St. George’s Magazine of January 1910, Ramsay Couper wrote of the decision to begin building that year:

A great work ... lies before us as we stand on the threshold of 1910. Let us go forward to it with zeal and confidence, always having in mind Him for whom we are working. Remember that this Church, which we hope to build, will not be something entirely for ourselves; we shall hand it down as a great gift to posterity. Long after we have passed away, others will use it, as we hope to use it, for the worship of our Heavenly Father; it will be to them, as to us, a centre of religious activity and religious work; they will come to regard it, as we may too, with feelings of reverence and affection, because within its walls they heard and received the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which He commanded to be preached to every creature.

South facing, in red brick and stone, St. George’s Church was conceived to accommodate 750, complete with a tower of 120 feet at the ritual south-west corner. It was decided to build in two stages, the first consisting of the chancel, choir, Lady Chapel, vestries and four of the envisaged five bays of the nave. The foundation stone was laid by Her Grace Adeline, Dowager Duchess of Bedford, on 27th October 1910. She made a return visit for the consecration of the new church by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London, on 7th October 1911. The building was able to accommodate 650 people (tightly packed) and it was recorded that at the service of consecration some 200 failed to gain admission.

In a 1947 report, Judith Scott of the Central Council for the Care of Churches said that she was ‘impressed with the dignity and fine proportions of the church’ and was ‘inclined to think that it is the best thing the architect has ever built. The architectural detail is in the true line of the Gothic tradition: he has used massive timbers and the best materials obtainable, and used them with great skill and a certain subtlety’. She thought it promised, when complete, to be one of the best early 20th century churches in the diocese.

£8,050 was eventually raised to pay for the main body of the church, of which £3,870 was received in grants, mostly from the Bishop of London’s Fund and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Contributors included the Dowager Duchess of Bedford, Lady Northwick, and Mr. Ambrose Heal Snr. – proprietor of the furnishing store in Tottenham Court Road, staunch Pinner churchman and, in 1897, patron of the Headstone Races in which his horse finished last.

An agreement dated 31st July 1911 between Frank Bealey and Arthur Winnington-Ingram vested the right of patronage and nominating the incumbent of St. George’s, Headstone in the Bishop of London and his successors. Ramsay Couper became Vicar of St. George’s on 4th December 1911. The following year a double-panelled window designed by Ninian Comper was installed in Pinner Parish Church depicting St. Anselm and St. George, the patron saints of the two daughter churches of Hatch End and Headstone.

The clearance of the debt on the church was made possible by the success of the huge ‘Bazaar of All Nations’ held on the 11th, 12th and 13th June 1913, opened by Her Highness Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein accompanied by Lady Edward Spencer-Churchill. Around 5,000 people visited the grand event; stalls were positioned in the field on the opposite side of Pinner View, lent by Mr. A. W. Hall of Headstone Manor Farm (known locally as Moat farm), and in the former temporary church. Initially, as well as a place of worship, this building had to serve as a venue for all church-related meetings and functions. Once the main part of the church was finished the temporary building was given over exclusively to social and educational use.

When this important question was under consideration, a small committee was appointed to inspect new churches in various parts of greater London. After visiting many buildings of different types the committee discovered a really fine church in the neighbourhood of Tottenham. They asked the Verger the name of the architect, and he told them it was Mr. J. S. Alder. Further specimens of his work confirmed the favourable impression, and Mr. Alder was appointed. Thus it was not by recommendation, but by merit alone that Mr. Alder was chosen, and we need hardly say we have every reason to congratulate ourselves on the choice.

John Samuel Alder (1847-1919) gained a reputation for combining sound building with economy to produce elegant, uncluttered churches. His work – Arts & Crafts-informed Gothic Revival, distinguished by a masterly handling of light and space – was much in demand at the end of the great period of suburban church building before the First World War. Most of his commissions came from within the Diocese of London.

In the St. George’s Magazine of January 1910, Ramsay Couper wrote of the decision to begin building that year:

A great work ... lies before us as we stand on the threshold of 1910. Let us go forward to it with zeal and confidence, always having in mind Him for whom we are working. Remember that this Church, which we hope to build, will not be something entirely for ourselves; we shall hand it down as a great gift to posterity. Long after we have passed away, others will use it, as we hope to use it, for the worship of our Heavenly Father; it will be to them, as to us, a centre of religious activity and religious work; they will come to regard it, as we may too, with feelings of reverence and affection, because within its walls they heard and received the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which He commanded to be preached to every creature.

South facing, in red brick and stone, St. George’s Church was conceived to accommodate 750, complete with a tower of 120 feet at the ritual south-west corner. It was decided to build in two stages, the first consisting of the chancel, choir, Lady Chapel, vestries and four of the envisaged five bays of the nave. The foundation stone was laid by Her Grace Adeline, Dowager Duchess of Bedford, on 27th October 1910. She made a return visit for the consecration of the new church by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London, on 7th October 1911. The building was able to accommodate 650 people (tightly packed) and it was recorded that at the service of consecration some 200 failed to gain admission.

In a 1947 report, Judith Scott of the Central Council for the Care of Churches said that she was ‘impressed with the dignity and fine proportions of the church’ and was ‘inclined to think that it is the best thing the architect has ever built. The architectural detail is in the true line of the Gothic tradition: he has used massive timbers and the best materials obtainable, and used them with great skill and a certain subtlety’. She thought it promised, when complete, to be one of the best early 20th century churches in the diocese.

£8,050 was eventually raised to pay for the main body of the church, of which £3,870 was received in grants, mostly from the Bishop of London’s Fund and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Contributors included the Dowager Duchess of Bedford, Lady Northwick, and Mr. Ambrose Heal Snr. – proprietor of the furnishing store in Tottenham Court Road, staunch Pinner churchman and, in 1897, patron of the Headstone Races in which his horse finished last.

An agreement dated 31st July 1911 between Frank Bealey and Arthur Winnington-Ingram vested the right of patronage and nominating the incumbent of St. George’s, Headstone in the Bishop of London and his successors. Ramsay Couper became Vicar of St. George’s on 4th December 1911. The following year a double-panelled window designed by Ninian Comper was installed in Pinner Parish Church depicting St. Anselm and St. George, the patron saints of the two daughter churches of Hatch End and Headstone.

The clearance of the debt on the church was made possible by the success of the huge ‘Bazaar of All Nations’ held on the 11th, 12th and 13th June 1913, opened by Her Highness Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein accompanied by Lady Edward Spencer-Churchill. Around 5,000 people visited the grand event; stalls were positioned in the field on the opposite side of Pinner View, lent by Mr. A. W. Hall of Headstone Manor Farm (known locally as Moat farm), and in the former temporary church. Initially, as well as a place of worship, this building had to serve as a venue for all church-related meetings and functions. Once the main part of the church was finished the temporary building was given over exclusively to social and educational use.

Organ and Great War

The organ at St. George's, Headstone, 1915

The organ at St. George's, Headstone, 1915

At St. Anne’s, Soho, Ramsay Couper had acted as ‘Precentor’, and he soon formed a choir of men and boys at St. George’s with himself as choirmaster for the time being. By January 1908 the choir numbered 31. In the beginning only a harmonium was available for services, but a rendering of Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’ on Good Friday 1908 was accompanied to by a single-manual organ of unrecorded manufacture, purchased from a Mr. Darvil of Windsor and installed by Mr. Frederick Rothwell. When the new church was built the single-manual organ was transferred to the organ loft until financial circumstances allowed the acquisition of a larger instrument.

It became possible to focus attention on the provision of a suitable organ in the summer of 1913. Five first-class organ builders were invited to tender for a three-manual instrument, including Frederick Rothwell (1853-1944), whose tender was accepted with a view to completion by 1st December 1914. At the time Rothwell was based in Clifton Road, Willesden Junction; in 1922 the firm moved to Bonnersfield Lane, Harrow, where it remained until its closure in 1960.

The detached console in Rothwell’s specification included his patented stop-key control system whereby stop-keys placed above each manual replaced the conventional stop-knobs on either side. Rothwell’s rebuilt Temple Church organ for Sir (Henry) Walford Davies in 1910 generated widespread interest in Rothwell’s console design, which Davies praised for allowing the player ‘to glide from stop-key to stop-key while still playing, without the slightest break in the musical thought and without the slightest turn of the head or any irrelevant muscular effort’.

It became possible to focus attention on the provision of a suitable organ in the summer of 1913. Five first-class organ builders were invited to tender for a three-manual instrument, including Frederick Rothwell (1853-1944), whose tender was accepted with a view to completion by 1st December 1914. At the time Rothwell was based in Clifton Road, Willesden Junction; in 1922 the firm moved to Bonnersfield Lane, Harrow, where it remained until its closure in 1960.

The detached console in Rothwell’s specification included his patented stop-key control system whereby stop-keys placed above each manual replaced the conventional stop-knobs on either side. Rothwell’s rebuilt Temple Church organ for Sir (Henry) Walford Davies in 1910 generated widespread interest in Rothwell’s console design, which Davies praised for allowing the player ‘to glide from stop-key to stop-key while still playing, without the slightest break in the musical thought and without the slightest turn of the head or any irrelevant muscular effort’.

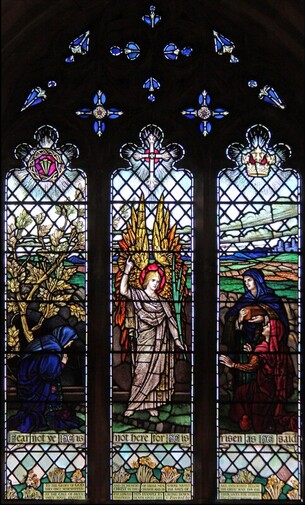

WW1 memorial window by William Aikman

WW1 memorial window by William Aikman

Jim Stewart observes that after the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 ‘the full enormity of the war was not felt at first and the magazines of 1914 and 1915 seem as much concerned about the new organ as in the events at the Front’. Progress on the organ was delayed by the war, and the service of dedication followed by the opening recital played by Sydney Toms of St. James’s, Piccadilly did not take place until 26th September 1915.

A large amount was still needed to pay for the instrument and it had been decided that, in view of the difficulties of the time, sums too small to be missed could be saved regularly and presented at the opening service. One envelope from France endorsed ‘from and the trenches’ contained five francs. By June 1919 £1,571 had been raised to finally pay for the organ.

The organist, Mr. Hubert Stearns, was not present at the dedication of the instrument as he was one of 63 members of the congregation to have enlisted by March 1915. ‘Nothing has struck me more than the splendid way in which the young men of the parish have responded to the call of patriotism’ the Vicar wrote in the St. George’s Magazine of January 1915. In the same month as the opening of the organ the people of St. George’s were informed of the death of Eric Stearns – brother of the organist and a former choirboy – who had been killed in action.

A stained glass window by William Aikman depicting the angel and women at the empty tomb was unveiled in the Lady Chapel on 17th July 1921 by Sir Philip Lloyd-Greame M.P. It is a memorial to those who ‘worshipped Christ in this church and in the days of the Great War 1914-18 at the call of duty followed His example by laying down their lives for others’. Below the window are the names of 18 members of the congregation.

A large amount was still needed to pay for the instrument and it had been decided that, in view of the difficulties of the time, sums too small to be missed could be saved regularly and presented at the opening service. One envelope from France endorsed ‘from and the trenches’ contained five francs. By June 1919 £1,571 had been raised to finally pay for the organ.

The organist, Mr. Hubert Stearns, was not present at the dedication of the instrument as he was one of 63 members of the congregation to have enlisted by March 1915. ‘Nothing has struck me more than the splendid way in which the young men of the parish have responded to the call of patriotism’ the Vicar wrote in the St. George’s Magazine of January 1915. In the same month as the opening of the organ the people of St. George’s were informed of the death of Eric Stearns – brother of the organist and a former choirboy – who had been killed in action.

A stained glass window by William Aikman depicting the angel and women at the empty tomb was unveiled in the Lady Chapel on 17th July 1921 by Sir Philip Lloyd-Greame M.P. It is a memorial to those who ‘worshipped Christ in this church and in the days of the Great War 1914-18 at the call of duty followed His example by laying down their lives for others’. Below the window are the names of 18 members of the congregation.

Vicarage, Meadow and Manor

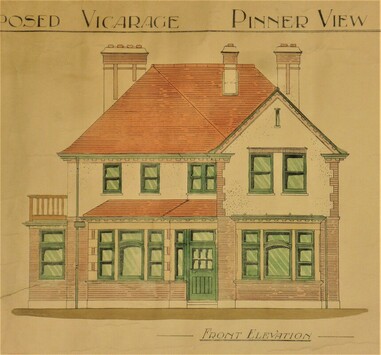

Design drawing of St. George's Vicarage by James A. Webb

Design drawing of St. George's Vicarage by James A. Webb

In 1914 the Bishop of the London’s Fund bought part of ‘middle water field’ – the location of the ‘Bazaar of All Nations’ – to accommodate a vicarage and permanent church hall; the site was enlarged by a further purchase in 1920.

Before the building of the vicarage and hall, however, there was an investigation by the Vicar’s Warden into the possibility of St. Georges acquiring more of the field. The church playing field initiative was presented to the congregation in the St. George’s Magazine of November 1922:

Last Summer Mr. John R. Newman initiated a scheme for acquiring some ground as a Church Recreation Field. Recently the scheme matured and we had the offer of the freehold of about three acres in the field opposite the Church for £500. The matter was brought before the Parochial Church Council at their last meeting and they unanimously agreed that the opportunity of acquiring such a piece of ground, which could be used for cricket, football, Fetes, Pet Shows, Flower Shows, was too good to be lost. No delay was possible, we had either to take the chance that presented itself, or to let it go for ever. We had no money in hand, but we decided to say ‘snap’ to the offer, and trust to the generosity of kind friends to help us find the amount. One has already come forward; we expect to see many others following in his train.

In purchasing the field the P.C.C. agreed that £200 should be advanced from the Church Hall Fund and any available balances at the bank, and that a sum of up to £300 could be borrowed from members of the congregation. Fundraising for the repayment of these loans continued until the middle of 1925. The P.C.C.’s decision to buy the land was fully vindicated by decades of use by the Church’s cricket and tennis clubs, and affiliated scouts and guides.

The man commissioned by the P.C.C. to design the new vicarage was James A. Webb, Director of Housing and Town Planning and Consulting Engineer to the Hendon Rural District Council (the local authority at the time covering Little and Great Stanmore, Harrow Weald, Pinner and Headstone). Webb’s Arts & Crafts-influenced design for the vicarage evoked the architectural style of the beginning of the century. His obituary in the Harrow Observer & Gazette of 11th September 1925 records that his association with the Council began 33 years before, and that ‘the Town Planning Scheme of the Council was conceived and worked out in all its detail by Mr. Webb’. Webb was well known to Ramsay Couper who first became a member of Hendon Rural District Council in April 1910 and who served continually until July 1925. Ramsay Couper was elected Chairman of the Council for 1914-1915, then again for 1923-1924.

Chief among the contributors to the vicarage building project were the Ecclesiastical Commissioners who at first met pound-for-pound sums raised from other sources – including £600 for the value of the land donated by the Bishop of London’s Fund. By 1921 the Commissioners had changed their policy, granting £7 for every £10 offered. St. George’s raised over £1,000 towards the final building and landscaping cost of approximately £3,200. The Vicar and his family took up residence in the newly-completed vicarage on 3rd September 1923, having previously lived at ‘St. George’s Lodge’, now 84 Pinner View.

In June 1911 the St. George’s Magazine had expressed relief that what survived of the Headstone Estate, including the house, had not been sold at the auction held on 26th May, when it was withdrawn from sale at £10,000.

Of course it is impossible to foresee the future; but it would seem that the forward march of bricks and mortar will, as a result, be delayed at least for the present. We sincerely hope that whenever the Estate does fall into the hands of the builder, a strong and successful effort will be made to secure the house and buildings to the public.

In 1924 – during the second period of Ramsay Couper’s chairmanship of the Council – the purchase of Headstone Manor and some 64 acres of land as public open space was raised for the first time and agreed.

At the end of September 1925 Ramsay Couper left St. George’s in an exchange of livings with the Rev. T. Barton Milton, Vicar of Boughton Monchelsea, near Maidstone. His farewell letter appeared in the St. George’s Magazine of that month:

My Dear Friends,

The days of my ministry among you are fast drawing to a close …

The climber does not realize his progress until he looks back; then he sees how far he has come. Looking back, it is difficult to believe that St. George’s is the same place it was 18 years ago. Then we had nothing but a bare piece of ground. Now we have a stately Church and a wide parochial organization. Then we had a handful of worshippers: now our Congregation not infrequently fills the Church. The Communicants last Easter Day numbered 626. Music has become an important and a helpful feature in our services. A keen interest has been awakened in Missionary work.

Nor have the requirements of the future been forgotten. A notable work has been done among the Young People with a view to building up future congregations; and to the same end, the Mothers Union, in which Mrs. Couper has taken a keen interest, has proved a most helpful organization. Again a Vicarage has been built, a playing field for the Young People purchased and a site for the new Church Hall acquired. No one man, of course, could have done all these things singlehanded, and, looking back, the thing that strikes me most is the number of splendid workers that have responded to the call for help, and that response has been the secret of our success.

Perhaps I may be allowed to say that, during the last 15 years, I have been a representative of Headstone on the Hendon Rural District Council. On that body it has always been my policy to work for the systematic and unified development of the district, and I am proud to have been associated with the decision to acquire the Moat Farm as an open space for all time. Whatever may be thought of such a policy today, I believe its results will be valued by future generations. …

May God bless you all.

Your affectionate friend, Ramsay W. Couper

Mrs. Phyllis Clough, who died in 2014 aged 96, remembered Ramsay Couper riding around the parish on a horse.

Before the building of the vicarage and hall, however, there was an investigation by the Vicar’s Warden into the possibility of St. Georges acquiring more of the field. The church playing field initiative was presented to the congregation in the St. George’s Magazine of November 1922:

Last Summer Mr. John R. Newman initiated a scheme for acquiring some ground as a Church Recreation Field. Recently the scheme matured and we had the offer of the freehold of about three acres in the field opposite the Church for £500. The matter was brought before the Parochial Church Council at their last meeting and they unanimously agreed that the opportunity of acquiring such a piece of ground, which could be used for cricket, football, Fetes, Pet Shows, Flower Shows, was too good to be lost. No delay was possible, we had either to take the chance that presented itself, or to let it go for ever. We had no money in hand, but we decided to say ‘snap’ to the offer, and trust to the generosity of kind friends to help us find the amount. One has already come forward; we expect to see many others following in his train.

In purchasing the field the P.C.C. agreed that £200 should be advanced from the Church Hall Fund and any available balances at the bank, and that a sum of up to £300 could be borrowed from members of the congregation. Fundraising for the repayment of these loans continued until the middle of 1925. The P.C.C.’s decision to buy the land was fully vindicated by decades of use by the Church’s cricket and tennis clubs, and affiliated scouts and guides.

The man commissioned by the P.C.C. to design the new vicarage was James A. Webb, Director of Housing and Town Planning and Consulting Engineer to the Hendon Rural District Council (the local authority at the time covering Little and Great Stanmore, Harrow Weald, Pinner and Headstone). Webb’s Arts & Crafts-influenced design for the vicarage evoked the architectural style of the beginning of the century. His obituary in the Harrow Observer & Gazette of 11th September 1925 records that his association with the Council began 33 years before, and that ‘the Town Planning Scheme of the Council was conceived and worked out in all its detail by Mr. Webb’. Webb was well known to Ramsay Couper who first became a member of Hendon Rural District Council in April 1910 and who served continually until July 1925. Ramsay Couper was elected Chairman of the Council for 1914-1915, then again for 1923-1924.

Chief among the contributors to the vicarage building project were the Ecclesiastical Commissioners who at first met pound-for-pound sums raised from other sources – including £600 for the value of the land donated by the Bishop of London’s Fund. By 1921 the Commissioners had changed their policy, granting £7 for every £10 offered. St. George’s raised over £1,000 towards the final building and landscaping cost of approximately £3,200. The Vicar and his family took up residence in the newly-completed vicarage on 3rd September 1923, having previously lived at ‘St. George’s Lodge’, now 84 Pinner View.

In June 1911 the St. George’s Magazine had expressed relief that what survived of the Headstone Estate, including the house, had not been sold at the auction held on 26th May, when it was withdrawn from sale at £10,000.

Of course it is impossible to foresee the future; but it would seem that the forward march of bricks and mortar will, as a result, be delayed at least for the present. We sincerely hope that whenever the Estate does fall into the hands of the builder, a strong and successful effort will be made to secure the house and buildings to the public.

In 1924 – during the second period of Ramsay Couper’s chairmanship of the Council – the purchase of Headstone Manor and some 64 acres of land as public open space was raised for the first time and agreed.

At the end of September 1925 Ramsay Couper left St. George’s in an exchange of livings with the Rev. T. Barton Milton, Vicar of Boughton Monchelsea, near Maidstone. His farewell letter appeared in the St. George’s Magazine of that month:

My Dear Friends,

The days of my ministry among you are fast drawing to a close …

The climber does not realize his progress until he looks back; then he sees how far he has come. Looking back, it is difficult to believe that St. George’s is the same place it was 18 years ago. Then we had nothing but a bare piece of ground. Now we have a stately Church and a wide parochial organization. Then we had a handful of worshippers: now our Congregation not infrequently fills the Church. The Communicants last Easter Day numbered 626. Music has become an important and a helpful feature in our services. A keen interest has been awakened in Missionary work.

Nor have the requirements of the future been forgotten. A notable work has been done among the Young People with a view to building up future congregations; and to the same end, the Mothers Union, in which Mrs. Couper has taken a keen interest, has proved a most helpful organization. Again a Vicarage has been built, a playing field for the Young People purchased and a site for the new Church Hall acquired. No one man, of course, could have done all these things singlehanded, and, looking back, the thing that strikes me most is the number of splendid workers that have responded to the call for help, and that response has been the secret of our success.

Perhaps I may be allowed to say that, during the last 15 years, I have been a representative of Headstone on the Hendon Rural District Council. On that body it has always been my policy to work for the systematic and unified development of the district, and I am proud to have been associated with the decision to acquire the Moat Farm as an open space for all time. Whatever may be thought of such a policy today, I believe its results will be valued by future generations. …

May God bless you all.

Your affectionate friend, Ramsay W. Couper

Mrs. Phyllis Clough, who died in 2014 aged 96, remembered Ramsay Couper riding around the parish on a horse.

Heaven and Hall

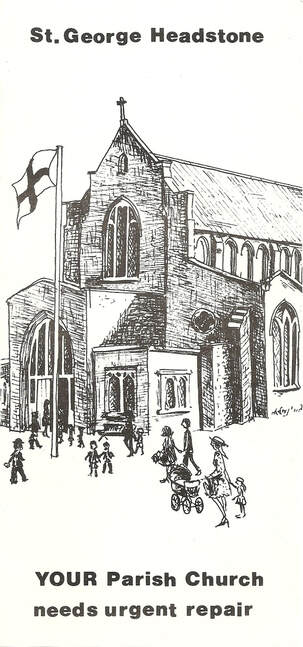

St. George's Hall

St. George's Hall

There was a congregation of around 1,000 when the Bishop of London visited St. George’s for Evensong on Sunday 13th June 1926. This was a time when diocesan bishops would to take time to visit their clergy. Winnington-Ingram was a firm believer in the salutary effects of frequent immersion, and vicarage child Hope Purchase, née Milton, remembered that he would arrive at the house expecting to be able to take a bath.

The Bishop must have been pleased to see the growth of St. George’s, which went hand-in-hand with housing development. The rapid increase in population is documented in the census returns: 2,818 residents in 1911 more than doubling to 6,088 in 1921, and then on to 11,532 in 1931. (The population remained at roughly the same level throughout the rest of the 20th century. In 2001 it was 11,065, but by 2011 it had risen to 13,720.)

An immediate priority for Barton Milton was the provision of a building to better accommodate the wide range of educational and recreational activities of a large and growing congregation. In 1926 a competition was carried out according to the advice of the Royal Institute of British Architects, assessed by William Henry Ansell. It was stated that the new hall should be built and furnished at a total cost of around £8,000. Three competitive designs were submitted; the one chosen was by Cyril Arthur Farey (1888-1954).

Farey was an accomplished architect: in 1924, with Graham Dawbarn, he had won a British Empire-wide competition for Raffles College, Singapore. He was also the leading architectural illustrator of the day, engaged by the likes of Edwin Lutyens and Frank Lloyd Wright to produce attractive technically accurate watercolours to promote their designs.

Based on his 1923 design for Holy Trinity Church Hall, Hounslow (built to a lower specification and later demolished for development), Cyril Farey’s scheme for St. George’s provided for a small hall, two classrooms, a kitchen, cloakrooms and lavatories on the ground floor, with a large hall, stage, dressing rooms and two-storey caretaker’s flat above. The small hall was to seat 200 and the large hall 500. The architectural style was Neo-Georgian, incorporating Art Deco features. In 1927 Farey’s watercolour of the design was exhibited at the Royal Academy and reproduced in black and white in The Builder.

Reduction in the size of the proposed building became necessary when the lowest builder’s tender submitted was almost £2,000 in excess of the budgeted sum. Thus the seating capacity of the small hall was reduced to 170 and the large hall to 400, according to standards of the time. The foundation stone was laid by distinguished lawyer and judge Lord Phillimore on 20th October 1928 and the opening ceremony, conducted by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, took place on 29th May 1929. Although it had been stipulated that the hall was to be built and furnished for £8,000, by the time the debt was cleared in December 1935 the cost had escalated to £10,261, of which approximately £8,000 had been raised by St. George’s. The temporary church-turned church hall was sold to Kodak Ltd. for use on its recreation ground. To see a video of the building of St. George’s Hall click here.

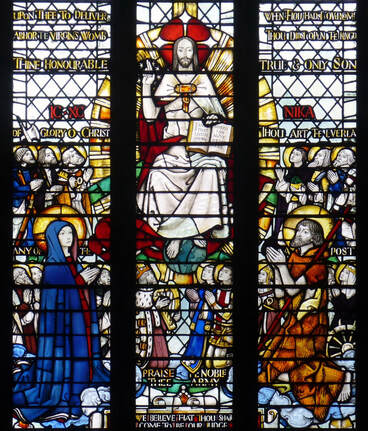

In May 1935 the P.C.C. learnt that an anonymous donor wished to provide a work of stained glass for the great east window. The matter was referred to the Diocesan Advisory Committee, who recommended the designer Martin Travers (1886-1948). Martin Travers (born Howard Martin Otho Travers) was awarded the Grand Prix for stained glass at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925 – the exhibition which gave rise to the term ‘Art Deco’. That same year he was appointed chief instructor in stained glass at the Royal College of Art – a position he held until his death. Art historian Peter Cormack considers him ‘perhaps the most influential British stained glass artist of the second quarter of the 20th century’.

Travers met with St. George’s P.C.C. on 15th October 1935 to present his ‘Te Deum’ design - depicting the worship of God in heaven and on earth. The design was accepted subject to one qualification: the deletion of Charles I among the ‘noble army of martyrs’ and his replacement with another saint. The minutes were agreed and signed at the next P.C.C. meeting, on 30th January – the anniversary of Charles’ execution and the old Book of Common Prayer festival of King Charles the Martyr. Travers substituted Charles with St. Edmund, another royal martyr.

The window was dedicated by the Rt. Rev. Guy Smith, Bishop of Willesden, on 7th March 1937. The design was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1938. Peter Cormack comments:

It is in his characteristic style of the 1930s, which blends elements derived from late 15th-century English/French stained glass with an attractively contemporary style of drawing. As always in Travers’ work, the lettering is beautifully designed and plays an important part in the overall design.

Widely recognised at the time as a major work by a leading artist, the east window was the beginning of the adornment of the church by Travers and his chief assistant John Crawford which, complementing the elegant and restrained architecture, has enhanced its beauty and distinction. For more information on the work of Travers and Crawford at St. George's click here.

The Bishop must have been pleased to see the growth of St. George’s, which went hand-in-hand with housing development. The rapid increase in population is documented in the census returns: 2,818 residents in 1911 more than doubling to 6,088 in 1921, and then on to 11,532 in 1931. (The population remained at roughly the same level throughout the rest of the 20th century. In 2001 it was 11,065, but by 2011 it had risen to 13,720.)

An immediate priority for Barton Milton was the provision of a building to better accommodate the wide range of educational and recreational activities of a large and growing congregation. In 1926 a competition was carried out according to the advice of the Royal Institute of British Architects, assessed by William Henry Ansell. It was stated that the new hall should be built and furnished at a total cost of around £8,000. Three competitive designs were submitted; the one chosen was by Cyril Arthur Farey (1888-1954).

Farey was an accomplished architect: in 1924, with Graham Dawbarn, he had won a British Empire-wide competition for Raffles College, Singapore. He was also the leading architectural illustrator of the day, engaged by the likes of Edwin Lutyens and Frank Lloyd Wright to produce attractive technically accurate watercolours to promote their designs.

Based on his 1923 design for Holy Trinity Church Hall, Hounslow (built to a lower specification and later demolished for development), Cyril Farey’s scheme for St. George’s provided for a small hall, two classrooms, a kitchen, cloakrooms and lavatories on the ground floor, with a large hall, stage, dressing rooms and two-storey caretaker’s flat above. The small hall was to seat 200 and the large hall 500. The architectural style was Neo-Georgian, incorporating Art Deco features. In 1927 Farey’s watercolour of the design was exhibited at the Royal Academy and reproduced in black and white in The Builder.

Reduction in the size of the proposed building became necessary when the lowest builder’s tender submitted was almost £2,000 in excess of the budgeted sum. Thus the seating capacity of the small hall was reduced to 170 and the large hall to 400, according to standards of the time. The foundation stone was laid by distinguished lawyer and judge Lord Phillimore on 20th October 1928 and the opening ceremony, conducted by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, took place on 29th May 1929. Although it had been stipulated that the hall was to be built and furnished for £8,000, by the time the debt was cleared in December 1935 the cost had escalated to £10,261, of which approximately £8,000 had been raised by St. George’s. The temporary church-turned church hall was sold to Kodak Ltd. for use on its recreation ground. To see a video of the building of St. George’s Hall click here.

In May 1935 the P.C.C. learnt that an anonymous donor wished to provide a work of stained glass for the great east window. The matter was referred to the Diocesan Advisory Committee, who recommended the designer Martin Travers (1886-1948). Martin Travers (born Howard Martin Otho Travers) was awarded the Grand Prix for stained glass at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925 – the exhibition which gave rise to the term ‘Art Deco’. That same year he was appointed chief instructor in stained glass at the Royal College of Art – a position he held until his death. Art historian Peter Cormack considers him ‘perhaps the most influential British stained glass artist of the second quarter of the 20th century’.

Travers met with St. George’s P.C.C. on 15th October 1935 to present his ‘Te Deum’ design - depicting the worship of God in heaven and on earth. The design was accepted subject to one qualification: the deletion of Charles I among the ‘noble army of martyrs’ and his replacement with another saint. The minutes were agreed and signed at the next P.C.C. meeting, on 30th January – the anniversary of Charles’ execution and the old Book of Common Prayer festival of King Charles the Martyr. Travers substituted Charles with St. Edmund, another royal martyr.

The window was dedicated by the Rt. Rev. Guy Smith, Bishop of Willesden, on 7th March 1937. The design was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1938. Peter Cormack comments:

It is in his characteristic style of the 1930s, which blends elements derived from late 15th-century English/French stained glass with an attractively contemporary style of drawing. As always in Travers’ work, the lettering is beautifully designed and plays an important part in the overall design.

Widely recognised at the time as a major work by a leading artist, the east window was the beginning of the adornment of the church by Travers and his chief assistant John Crawford which, complementing the elegant and restrained architecture, has enhanced its beauty and distinction. For more information on the work of Travers and Crawford at St. George's click here.

Second World War

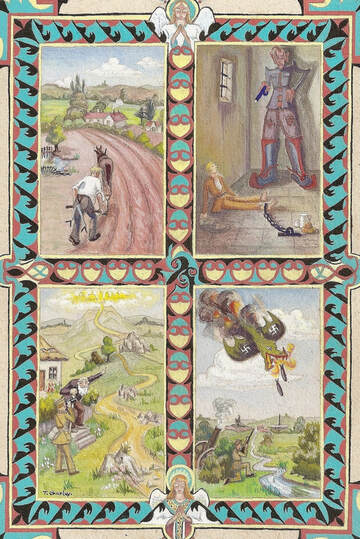

The legend of St. George by Thelma Charley

The legend of St. George by Thelma Charley

The major theme of the St. George’s Magazine of October 1939 was the outbreak of war. The Vicar assured parishioners that in the suddenly changed circumstances ‘my first wish and duty is to adapt the ministry and services of the Church in this parish to meet your needs’.

‘Being unworthy of peace we find ourselves at war again - a war which will profoundly affect the life of each one of us’ wrote Mr. A. J. Lambert, Deputy Churchwarden and Chairman of the five year old Harrow Urban District Council. In 1942 the railings round the church donated by Mr. Lambert in 1933 were requisitioned for munitions.

Another contribution to the magazine of October 1939 was from curate the Rev. Joseph H. Warren, who had been a chaplain to the forces during the Great War:

Whether your loved one went to Church or not when at home, you can be certain that ‘out there’ or wherever he is, the natural instinct for God sooner or later finds expression. He will pray. He will pray for you, your love and protection. Now, this is where you come in. You, too, must pray … for him, indeed there is much you can pray for – we shall try and help you in this direction. Remember, too, that he will be given opportunities to make his communion, it may be in a barn, a trench or even a dug-out – but the chaplains will see that the opportunity is given. You, too, must make your communions and make them regularly. This service is the great prayer meeting of the Church. It is here that we plead the Great Sacrifice of Christ for men and it is here that our blessed Lord gives Himself for the strengthening and preservation of both body and soul.

‘Bunny’ Warren asked for help in compiling a list of men and women of the parish serving with the armed forces and nursing services. They were to be remembered in prayer ‘and especially at the altar’. A leather-bound Roll of Honour was produced, the cover bearing words of St Paul: ‘Brethren, Pray For Us’. Inside, choir member Miss Thelma Charley presented ‘The Legend of St. George, adapted from Spencer’s Faerie Queen’ in four illustrations: Saint George ploughs his father’s field, Saint George in the dungeon of the giant Pride (sporting swastikas), The hermit Contemplation points out to Saint George (in British uniform) the way to the City of God, and Saint George kills the (bomb-spewing) Dragon. Joseph Warren left St. George’s in 1941, and in 1952 followed in the footsteps of T. Barton Milton and Ramsay Couper by becoming Vicar of Boughton Monchelsea.

‘Being unworthy of peace we find ourselves at war again - a war which will profoundly affect the life of each one of us’ wrote Mr. A. J. Lambert, Deputy Churchwarden and Chairman of the five year old Harrow Urban District Council. In 1942 the railings round the church donated by Mr. Lambert in 1933 were requisitioned for munitions.

Another contribution to the magazine of October 1939 was from curate the Rev. Joseph H. Warren, who had been a chaplain to the forces during the Great War:

Whether your loved one went to Church or not when at home, you can be certain that ‘out there’ or wherever he is, the natural instinct for God sooner or later finds expression. He will pray. He will pray for you, your love and protection. Now, this is where you come in. You, too, must pray … for him, indeed there is much you can pray for – we shall try and help you in this direction. Remember, too, that he will be given opportunities to make his communion, it may be in a barn, a trench or even a dug-out – but the chaplains will see that the opportunity is given. You, too, must make your communions and make them regularly. This service is the great prayer meeting of the Church. It is here that we plead the Great Sacrifice of Christ for men and it is here that our blessed Lord gives Himself for the strengthening and preservation of both body and soul.

‘Bunny’ Warren asked for help in compiling a list of men and women of the parish serving with the armed forces and nursing services. They were to be remembered in prayer ‘and especially at the altar’. A leather-bound Roll of Honour was produced, the cover bearing words of St Paul: ‘Brethren, Pray For Us’. Inside, choir member Miss Thelma Charley presented ‘The Legend of St. George, adapted from Spencer’s Faerie Queen’ in four illustrations: Saint George ploughs his father’s field, Saint George in the dungeon of the giant Pride (sporting swastikas), The hermit Contemplation points out to Saint George (in British uniform) the way to the City of God, and Saint George kills the (bomb-spewing) Dragon. Joseph Warren left St. George’s in 1941, and in 1952 followed in the footsteps of T. Barton Milton and Ramsay Couper by becoming Vicar of Boughton Monchelsea.

High altar reredos by John E. Crawford

High altar reredos by John E. Crawford

The defeat of the dragon is a prominent feature of Elkington’s impressive copper and silver-plated reproductions of Léonard Morel-Ladeuil’s large shield of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’– one of which was adopted as a challenge trophy by the London Diocesan Young People’s Temperance Guild. Churchwarden John R. Newman, who was founder and Secretary of the Guild, began meetings at St. George’s in late 1915. They offered a wide variety of social activities and lasted until 1941. Membership was open to young people aged between 14 and 21; those over 21 could attend but were ineligible to take part in competitions. The St. George’s branch first won the shield in 1918. In 1921 St. George’s fielded 114 candidates for temperance testing. In 1940, having won the shield for 23 consecutive years, St. George’s was allowed to keep it. John Christie noted in 1961 that it was hanging in the choir vestry ‘where perhaps it is intended to provide an inspiration to the choir’. It is now positioned on the west wall.

Following the outbreak of Western Front hostilities the church hall was used as a staging post for refugees arriving from Holland and Belgium. There they received a welcome and a meal before dispersal to their new billets. The first floor hall was later requisitioned for the storage of bombed-out furniture.

T. Barton Milton postponed his retirement at the behest of the Bishop of London who, in view of the number of younger men offering themselves as chaplains to the forces, called for older clergy to stay in their posts. He eventually announced his impending departure in February 1947, having led St. George’s for over 21 years including the time of its greatest numerical strength. 1934 saw 842 communicants on Easter Day, the largest number in the history of St. George’s. Membership of the church’s electoral roll was at its height in the late 1930s, with 727 enrolled in 1938 and 725 in 1939.

Barton Milton was succeeded in 1947 by the Rev. George Appleton – lately Archdeacon of Rangoon, later Archbishop in Jerusalem. T. Barton Milton returned to St. George’s to dedicate the Second World War Memorial on 26th June 1949. Designed by John Crawford to complement Travers’ great east window, it comprises a large triptych of the Epiphany and Annunciation above the high altar, flanked by a plaque of St. George slaying the dragon and a stone memorial tablet. The tablet commemorates 32 parishioners killed on active service, and also the ‘men, women and children of this parish who lost their lives through enemy action’. Among the names is Donald J. B. Milton, the Rev. T. Barton Milton’s elder son, killed in 1945. Nearly £670 of the £750 cost was contributed by the people of the parish.

Following the outbreak of Western Front hostilities the church hall was used as a staging post for refugees arriving from Holland and Belgium. There they received a welcome and a meal before dispersal to their new billets. The first floor hall was later requisitioned for the storage of bombed-out furniture.

T. Barton Milton postponed his retirement at the behest of the Bishop of London who, in view of the number of younger men offering themselves as chaplains to the forces, called for older clergy to stay in their posts. He eventually announced his impending departure in February 1947, having led St. George’s for over 21 years including the time of its greatest numerical strength. 1934 saw 842 communicants on Easter Day, the largest number in the history of St. George’s. Membership of the church’s electoral roll was at its height in the late 1930s, with 727 enrolled in 1938 and 725 in 1939.

Barton Milton was succeeded in 1947 by the Rev. George Appleton – lately Archdeacon of Rangoon, later Archbishop in Jerusalem. T. Barton Milton returned to St. George’s to dedicate the Second World War Memorial on 26th June 1949. Designed by John Crawford to complement Travers’ great east window, it comprises a large triptych of the Epiphany and Annunciation above the high altar, flanked by a plaque of St. George slaying the dragon and a stone memorial tablet. The tablet commemorates 32 parishioners killed on active service, and also the ‘men, women and children of this parish who lost their lives through enemy action’. Among the names is Donald J. B. Milton, the Rev. T. Barton Milton’s elder son, killed in 1945. Nearly £670 of the £750 cost was contributed by the people of the parish.

Church Completion and 'Spiritual 'Flu'

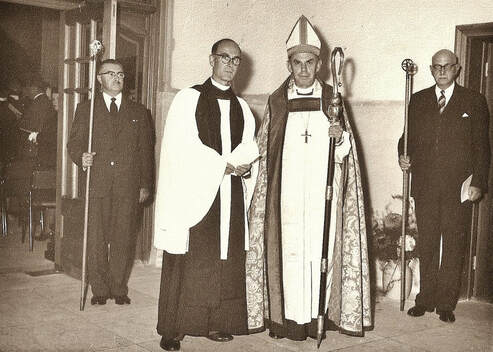

8th October 1961

8th October 1961

George Appleton’s brief period as incumbent was marked by a renewed emphasis on mission. The St. George’s Missionary Association had been active since 1924 and in 1947 raised 16% of the church’s income for foreign mission. There was a concentration of effort closer to home in the Mission to London of May 1949, for which St. George’s joined with Holy Trinity, Wealdstone in providing a centre. After the disruptions of war and in the wake of the Mission to London, early 1950s electoral roll membership and Easter communicants returned to levels seen in the 1930s. The Vicar who presided over this period of consolidation was the Rev. Christopher C. R. Goddard, formerly Curate-in-Charge of St. Barnabas, St. Marylebone, who was instituted in February 1950.

Since 1911 St. George’s vicars had been assisted by curates living in rented accommodation. 27 Parkside Way was purchased as a curates’ house in November 1947; in 1952 it was sold and 152 Pinner View, considered more suitable for the purpose, was acquired.

Christopher Goddard was succeeded as Vicar by the Rev. (Richard) John Vaughan in 1955. At Oxford he gained a first in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and a distinction in the Diploma in Theology. During the war he served as a chaplain to the forces, was mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the Military Cross. John Vaughan came to St. George’s from St Saviour’s, Alexandra Park, Wood Green – another church designed by J. S. Alder – where he had been Perpetual Curate.

Mrs. Margaret Vaughan later recalled:

We’d only been in the vicarage a matter of days, when Mr. Altman, the Churchwarden called one morning. As usual, John was out so after a few words of welcome, he said, ‘Now that you’re here, I hope you’ve come to stay. We’ve just had two short-term vicars, and we don’t want another’. The reply went out ‘Mr. Altman, now that we are here I’m not moving for ten years!’

The Vaughans would remain at St. George’s until John’s retirement 26 years later.

October 1957 – the 50th anniversary of the dedication of the temporary church – launched St. George’s on the campaign to complete the church building in time for the 50th anniversary of its consecration. Plans for finishing the church were presented at the Annual Parochial Church Meeting of 1960. The idea of a tower was dispensed with. The nave was to be enlarged by the length of a smaller bay, similar to Alder’s design for the west end of neighbouring St. John’s, Greenhill, and the building would also be extended by a narthex with the additional facilities of a meeting room, lavatories and store room (since converted into a kitchen). The scheme, devised by church member Arthur Betts, was placed in the hands of architect Robert John York of Hood, Huggins & York.

Although the contract with the builder stipulated completion by 14th March 1961, the work was finally finished in December 1962, costing well in excess of the estimated figure of £19,000. There were no longer large grants available from the Diocese and Commissioners and the money was raised by the people of the parish and by the receipt of a generous legacy. The church was packed for the dedication on 8th October 1961 by the Rt. Rev. Robert Stopford, Bishop of London, with the service relayed to an overflow congregation in the church hall.

A Parish Mission was held in Holy Week 1960, during which volunteers visited some 1,400 homes of people with some connection with St. George’s. George Appleton returned to play a leading part. But this did not arrest the decline in the number of Easter communicants and the membership of the electoral roll. In 1961 the electoral roll figure of 548 represented the first under 600 since the 1920s. By 1973 this had fallen to 213. 1963 saw the number of Easter communicants below 500 for the first time since 1921; ten years later it had halved to 238. The fall in support for the Church of England was a national phenomenon. At St. George’s this appears to have been exacerbated by demographic and recreational factors.

Since 1911 St. George’s vicars had been assisted by curates living in rented accommodation. 27 Parkside Way was purchased as a curates’ house in November 1947; in 1952 it was sold and 152 Pinner View, considered more suitable for the purpose, was acquired.

Christopher Goddard was succeeded as Vicar by the Rev. (Richard) John Vaughan in 1955. At Oxford he gained a first in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and a distinction in the Diploma in Theology. During the war he served as a chaplain to the forces, was mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the Military Cross. John Vaughan came to St. George’s from St Saviour’s, Alexandra Park, Wood Green – another church designed by J. S. Alder – where he had been Perpetual Curate.

Mrs. Margaret Vaughan later recalled:

We’d only been in the vicarage a matter of days, when Mr. Altman, the Churchwarden called one morning. As usual, John was out so after a few words of welcome, he said, ‘Now that you’re here, I hope you’ve come to stay. We’ve just had two short-term vicars, and we don’t want another’. The reply went out ‘Mr. Altman, now that we are here I’m not moving for ten years!’

The Vaughans would remain at St. George’s until John’s retirement 26 years later.

October 1957 – the 50th anniversary of the dedication of the temporary church – launched St. George’s on the campaign to complete the church building in time for the 50th anniversary of its consecration. Plans for finishing the church were presented at the Annual Parochial Church Meeting of 1960. The idea of a tower was dispensed with. The nave was to be enlarged by the length of a smaller bay, similar to Alder’s design for the west end of neighbouring St. John’s, Greenhill, and the building would also be extended by a narthex with the additional facilities of a meeting room, lavatories and store room (since converted into a kitchen). The scheme, devised by church member Arthur Betts, was placed in the hands of architect Robert John York of Hood, Huggins & York.

Although the contract with the builder stipulated completion by 14th March 1961, the work was finally finished in December 1962, costing well in excess of the estimated figure of £19,000. There were no longer large grants available from the Diocese and Commissioners and the money was raised by the people of the parish and by the receipt of a generous legacy. The church was packed for the dedication on 8th October 1961 by the Rt. Rev. Robert Stopford, Bishop of London, with the service relayed to an overflow congregation in the church hall.

A Parish Mission was held in Holy Week 1960, during which volunteers visited some 1,400 homes of people with some connection with St. George’s. George Appleton returned to play a leading part. But this did not arrest the decline in the number of Easter communicants and the membership of the electoral roll. In 1961 the electoral roll figure of 548 represented the first under 600 since the 1920s. By 1973 this had fallen to 213. 1963 saw the number of Easter communicants below 500 for the first time since 1921; ten years later it had halved to 238. The fall in support for the Church of England was a national phenomenon. At St. George’s this appears to have been exacerbated by demographic and recreational factors.

The Metropolitan Railway’s Metro-land of 1920 held out the promise that

the strain which the London business or professional man has to undergo amidst the turmoil and bustle of Town can only be counter-acted by the quiet restfulness and comfort of a residence amidst pure air and rural surroundings, and whilst jaded vitality and taxed nerves are the natural penalties of modern conditions, Nature has, in the delightful districts abounding in Metro-land, placed a potential remedy ready at hand.

As development continued apace the allure of green pastures drew many commuters and people retiring out of the increasingly congested Middlesex suburbs. This included pioneers of St. George’s. There was always a high turnover in the local population but thanks, in great measure, to its unusually extensive recreational facilities and social activities, in the 1930s – by which time housing development in the parish had paused – St. George’s experienced growing numbers against the national trend. Correspondingly, changes in society which accompanied the economic boom of the 1950s and which accelerated in the 1960s, had a marked effect. With the growth of consumerism and a wider choice of leisure activities fewer people were now making the church and its activities a focus of their lives.

‘One of the things we are slowly realising is that there is a strange infection creeping over society, rather like a spiritual ‘flu.’ So began the Vicar’s Letter in the St. George’s Magazine of February 1973. ‘It is affecting everything, mixing up our values and bringing people to the point of wondering if there is any distinction between good and evil. Vision gets so blurred that anything may pass … It causes divisions and these grow into enmities which could tear our society apart.’ Through the 1960s and early 1970s the Vicar’s Letter noted and berated changes taking place in society, as ‘outmoded’ values, standards and beliefs were abandoned:

Easy Money (October 1960) One thing has alarmed me this year, since time and time again the talk has turned to one subject. And that is ‘easy money’. It usually arises from property deals and then goes on to all sorts and ways of landing some windfall which comes by chance or clever dealing. This does betray a changed view of money … For a Christian there must be a fair relation of the claim made on the community by the money gained, and the contribution put in, in terms of effect and inspiration. In fact, it has been said that a gentleman is one who puts in more than he takes out: and that would set up a new and very varied class in the community. And a Christian stand in this matter is well due now, in order to stop the rot.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover (December 1960) It is true that serious students of literature should have access to the full text: that degree of freedom is good because directed to serious use. What is bad is that the choice of this book for public trial has set it free as reading matter for all and sundry. In it ... modesty and reticence ... are thrown aside making common what should be sacred … Freedom for self-expression in any way is not true self-realisation but brings about perversions which are real bondage. This leads to the Christian conclusion that only in the service of God and His purposes is there true freedom, when all our faculties are devoted to His use.

Public Service (May 1962) Real teachers are not bought: putting more money in does not necessarily bring more leaders out. Teaching, like leadership in all the professions, is a calling: it requires more than a down-payment to get the goods in this case. The service they render cannot be measured in terms of cash, though no one should wish them to get less than others doing comparable jobs. And we shall only get people of this type if the general ideals of service are high: if everyone is grubbing for the last penny for him or her self, we cannot expect to produce selfless servants of the community. Those who live by the creed ‘I’m all right Jack’, even if they don’t profess it, are in fact weighing down our common life until it becomes a total rat-race.