Martin Travers and John Crawford at St George's, Headstone

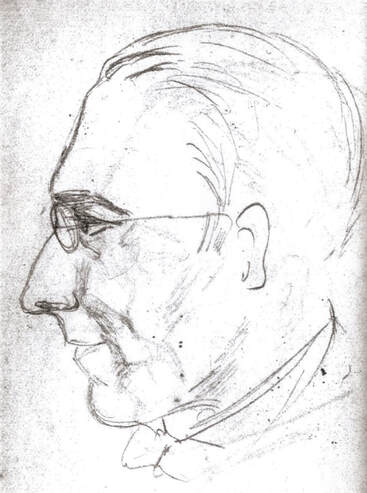

Martin Travers: self-portrait

Martin Travers: self-portrait

The main body of St George’s, Headstone, designed by J S Alder, was consecrated in 1911. Two world wars and the priorities of building a vicarage and church hall delayed the church’s completion for fifty years. Much of the attractive and cohesive character of the interior derives from the rich ensemble of glass and furnishings by leading ecclesiastical artist and designer Martin Travers (1886-1948) and his long-standing chief assistant John E Crawford (1897-1982). The process of commissioning and acquiring these works culminated as recently as 2018 with the addition of a significant and hitherto unknown set of wood carvings from the Travers studio.

The east window

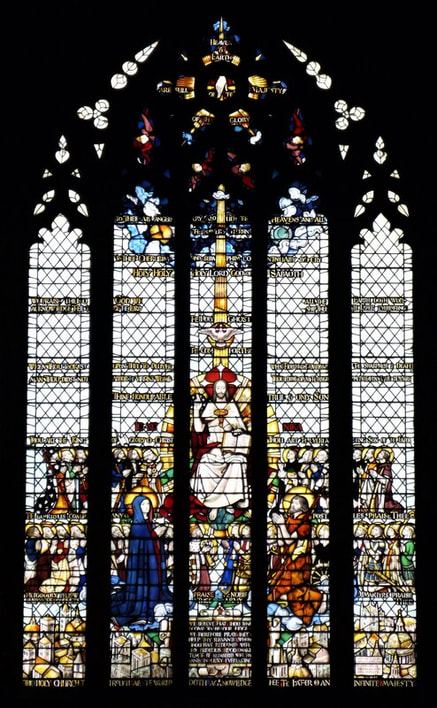

In May 1935 the Parochial Church Council learnt that an anonymous donor wished to provide a new window for the church and in July it was reported that Martin Travers, who had been recommended by the London Diocesan Advisory Committee, had visited the building. He was of the opinion that a window could be placed over the high altar for £600.

Travers met with the PCC in October to present his design. Tendering its best thanks the Council accepted the plan but requested that the figure of Charles I be substituted by that of another martyr. The minutes were signed on 30th January 1936, the anniversary of Charles’s execution. The east window was dedicated on 7th March 1937 and the design was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1938.

Lowndes & Drury of Fulham charged £214 for supplying, cutting, firing and leading the window. (In 1938 the firm charged £113 for their part in making Travers’ other very large five-lights and tracery window – for the great hall of Canterbury College, Christchurch, New Zealand.)

The level of assistance of former pupil-assistant Francis Spear is likely to have been substantial as the Lowndes & Drury order book lists the job under his name. Spear researcher Alan Brooks concludes that

he must have had a significant hand in making the window, almost certainly in its painting. Certainly it must have greatly influenced him because many of its features are adopted by Spear in later windows: hierarchical groupings of figures in a diagrammatic arrangement, cityscape sections, excellent lettering, good colour balance but with clear quarry areas, and the figure style which is still well-drawn but heading towards a more simplified contemporary mode.

Martin Travers’ account of the design appeared in the Parish Magazine of April 1937. The following description draws on Travers’ explanation and the work of The Arts Society.

The theme of the window is the Te Deum as found in Morning Prayer in The Book of Common Prayer. Travers comments that the verses incorporated in the design serve a decorative and explanatory purpose but that it is ‘not intended to be so obvious that he “who runs may read”’. The quotation is from the poem for Septuagesima in John Keble’s The Christian Year (There is a book, who runs may read …) which, like the Te Deum, speaks of the worship and service of God on earth and in heaven.

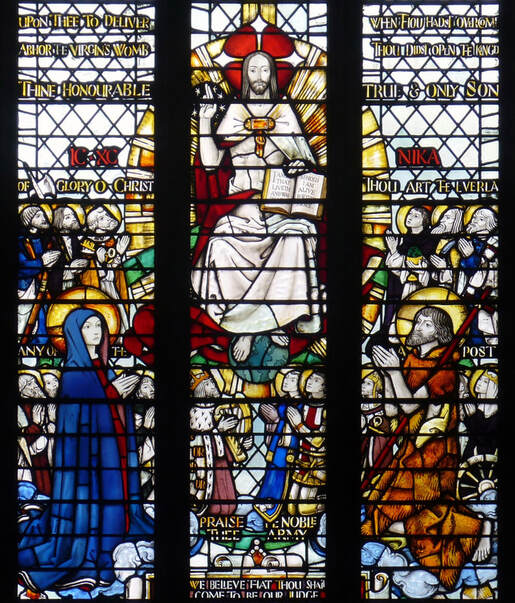

The central group of tracery lights depicts the Hand of God amid rays of glory, suggesting blessing, power and guidance and symbolizing THE FATHER OF AN INFINITE MAJESTY; there are four cherubs, each consisting of a head and red and pink wings – TO THEE ALL ANGELS CRY ALOUD THE HEAVENS AND ALL THE POWERS THEREIN – all against a blue sky with white stars and blue and white clouds. The Hand of God against a yellow cruciform is contained in a yellow-bordered red roundel. A yellow ray of light descending from the Hand of God streams down towards the head of Christ – THINE HONOURABLE TRUE AND ONLY SON.

In the starry firmament to the left of the ray of light is a yellow sun and to the right is a white-rayed blue moon. Superimposed on the ray of light, just above Christ’s halo, is a yellow-rayed roundel containing the white Holy Dove – THE HOLY GHOST THE COMFORTER – with a red and white cruciform halo. The Dove’s yellow feet are shown ready to land.

Christ in majesty as Lord and Redeemer is seated on the emerald rainbow (Rev 4:3) within a yellow-rayed mandorla with his feet resting on the globe of the world (Isa 66:1). His red halo has a white cross, patty fitchy, and he is wearing a red-lined white cloak draped over the lower part of his body leaving his chest bare. It is fastened at the neck with a rectangular yellow clasp and ties. His right hand is raised in blessing and nimbed with seven white stars on a black roundel (Rev 1:16). His left hand rests on an open book with yellow-edged pages displaying text from Rev 1:18: I AM HE THAT LIVETH AND WAS DEAD AND BEHOLD I AM ALIVE FOR EVERMORE. Flanking the mandorla is the sacred monogram for Jesus Christ Victor in red capitals on a black band: IC XC NIKA.

The east window

In May 1935 the Parochial Church Council learnt that an anonymous donor wished to provide a new window for the church and in July it was reported that Martin Travers, who had been recommended by the London Diocesan Advisory Committee, had visited the building. He was of the opinion that a window could be placed over the high altar for £600.

Travers met with the PCC in October to present his design. Tendering its best thanks the Council accepted the plan but requested that the figure of Charles I be substituted by that of another martyr. The minutes were signed on 30th January 1936, the anniversary of Charles’s execution. The east window was dedicated on 7th March 1937 and the design was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1938.

Lowndes & Drury of Fulham charged £214 for supplying, cutting, firing and leading the window. (In 1938 the firm charged £113 for their part in making Travers’ other very large five-lights and tracery window – for the great hall of Canterbury College, Christchurch, New Zealand.)

The level of assistance of former pupil-assistant Francis Spear is likely to have been substantial as the Lowndes & Drury order book lists the job under his name. Spear researcher Alan Brooks concludes that

he must have had a significant hand in making the window, almost certainly in its painting. Certainly it must have greatly influenced him because many of its features are adopted by Spear in later windows: hierarchical groupings of figures in a diagrammatic arrangement, cityscape sections, excellent lettering, good colour balance but with clear quarry areas, and the figure style which is still well-drawn but heading towards a more simplified contemporary mode.

Martin Travers’ account of the design appeared in the Parish Magazine of April 1937. The following description draws on Travers’ explanation and the work of The Arts Society.

The theme of the window is the Te Deum as found in Morning Prayer in The Book of Common Prayer. Travers comments that the verses incorporated in the design serve a decorative and explanatory purpose but that it is ‘not intended to be so obvious that he “who runs may read”’. The quotation is from the poem for Septuagesima in John Keble’s The Christian Year (There is a book, who runs may read …) which, like the Te Deum, speaks of the worship and service of God on earth and in heaven.

The central group of tracery lights depicts the Hand of God amid rays of glory, suggesting blessing, power and guidance and symbolizing THE FATHER OF AN INFINITE MAJESTY; there are four cherubs, each consisting of a head and red and pink wings – TO THEE ALL ANGELS CRY ALOUD THE HEAVENS AND ALL THE POWERS THEREIN – all against a blue sky with white stars and blue and white clouds. The Hand of God against a yellow cruciform is contained in a yellow-bordered red roundel. A yellow ray of light descending from the Hand of God streams down towards the head of Christ – THINE HONOURABLE TRUE AND ONLY SON.

In the starry firmament to the left of the ray of light is a yellow sun and to the right is a white-rayed blue moon. Superimposed on the ray of light, just above Christ’s halo, is a yellow-rayed roundel containing the white Holy Dove – THE HOLY GHOST THE COMFORTER – with a red and white cruciform halo. The Dove’s yellow feet are shown ready to land.

Christ in majesty as Lord and Redeemer is seated on the emerald rainbow (Rev 4:3) within a yellow-rayed mandorla with his feet resting on the globe of the world (Isa 66:1). His red halo has a white cross, patty fitchy, and he is wearing a red-lined white cloak draped over the lower part of his body leaving his chest bare. It is fastened at the neck with a rectangular yellow clasp and ties. His right hand is raised in blessing and nimbed with seven white stars on a black roundel (Rev 1:16). His left hand rests on an open book with yellow-edged pages displaying text from Rev 1:18: I AM HE THAT LIVETH AND WAS DEAD AND BEHOLD I AM ALIVE FOR EVERMORE. Flanking the mandorla is the sacred monogram for Jesus Christ Victor in red capitals on a black band: IC XC NIKA.

‘Te Deum’ east window by Martin Travers

‘Te Deum’ east window by Martin Travers

On Christ’s right kneel six of THE GLORIOUS COMPANY OF THE APOSTLES and on his left six more. Each has a yellow halo. Described from the viewer’s left to right are:

Below Christ on his right kneels the Blessed Virgin Mary – THOU DIDST NOT ABHOR THE VIRGIN’S WOMB. She has a yellow halo and wears a pink-lined red gown with a blue mantle drawn up to cover her head. It has a white border. Opposite her kneels St John the Baptist – THOU DIDST OPEN THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN TO ALL BELIEVERS (through baptism). He has a yellow halo and is clothed in camel skin with his red cross-staff leaning against his left shoulder. Each figure kneels on a blue cloud. Behind them are THE GOODLY FELLOWSHIP OF THE PROPHETS to Christ’s right and THE NOBLE ARMY OF MARTYRS to Christ’s left.

- St James the Great dressed in a yellow robe beneath a black cloak patterned with white scallop shells. There is a white scallop shell on his black hat and a pilgrim’s staff is propped against his right shoulder.

- St Paul in a green robe and a white cloak and holding a sword between his praying hands.

- St Thomas wearing a white robe and a red cloak, with his spear tucked under his right arm.

- St Andrew with a white cloak and a blue robe and holding his saltire cross between his arms.

- St Jude (or St Matthias) in a white robe and a brown cloak with his halberd leaning against his right shoulder.

- St Peter dressed in a white robe and yellow cloak and carrying two keys in his right hand.

- St John the Evangelist wearing a white robe and a purple cloak and carrying a yellow cup containing a green winged serpent.

- St Bartholomew in a white robe and yellow cloak and carrying a flaying knife between his praying hands.

- St Matthew wearing a blue robe and a white cloak. His Gospel in the form of a scroll tied with red banding is held against his left shoulder. Below lies an open scroll depicting his discarded accounts.

- A partially obscured figure in a white robe and blue cloak with no visible attribute.

- St Matthias (or St Jude) dressed in a yellow robe and white cloak with a halberd held between his praying hands, the head of which is resting on the ground.

- St James the Less in a white robe and light maroon cloak with his fuller’s club leaning against his left shoulder

Below Christ on his right kneels the Blessed Virgin Mary – THOU DIDST NOT ABHOR THE VIRGIN’S WOMB. She has a yellow halo and wears a pink-lined red gown with a blue mantle drawn up to cover her head. It has a white border. Opposite her kneels St John the Baptist – THOU DIDST OPEN THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN TO ALL BELIEVERS (through baptism). He has a yellow halo and is clothed in camel skin with his red cross-staff leaning against his left shoulder. Each figure kneels on a blue cloud. Behind them are THE GOODLY FELLOWSHIP OF THE PROPHETS to Christ’s right and THE NOBLE ARMY OF MARTYRS to Christ’s left.

Detail of Martin Travers east window

Detail of Martin Travers east window

Eight of the nine prophets kneeling to Christ’s right have no attributes, so cannot be identified, but they each have a yellow hexagonal halo indicating that they are Old Testament figures. They are described from the viewer’s left to right as wearing: 1. a blue robe and white cloak; 2. a yellow-bordered white cloak held with a circular brooch, over a light-maroon robe; 3. a white and yellow-striped cloak over a red robe; 4. a blue robe and a white cloak fastened with a circular yellow pearl-bordered brooch; 5. only a small portion of this figure can be seen; 6. a light-maroon robe and white cloak; 7. a white robe (but mainly behind the Virgin); 8. a green robe and yellow-bordered white cloak (in front of the Virgin). Beneath Christ’s feet to the right is King David in a light-maroon robe and ermine cloak. The cloak is embroidered with the yellow monogram DR (David Rex) and he is playing a harp.

Opposite the prophets are the kneeling martyrs, each with a yellow halo. From the viewer’s left to right are:

At the foot of the central light is a scrolled cartouche with text on a multi-coloured background. Behind the cartouche and stretching across all five lights is a panorama of churches and cathedrals – THE HOLY CHURCH THROUGHOUT ALL THE WORLD – against a blue sky and green hills. Travers mentions that these buildings include the Duomo, Florence; Notre Dame, Paris; Canterbury Cathedral; and St Paul’s, London. These remain the only buildings identified to date. In a white rectangle to the left of St Paul’s is the inscription: GIVEN FOR THE ADORNMENT OF GOD’S HOUSE BY A MEMBER OF THIS CONGREGATION ANNO D-M-NI 1936.

In 1998 art historian Peter Cormack visited St George’s and drew attention to the significance of the work by Travers and Crawford. Following the visit he wrote that ‘unlike Comper – the other well-known luminary in the field and under whom Travers trained for a while – Travers was committed to an original and modern interpretation of diverse stylistic traditions’. The window ‘is in his characteristic style of the 1930s, which blends elements derived from late 15th-century English/French stained glass with an attractively contemporary style of drawing. As always with Travers’ work, the lettering is beautifully designed and plays an important part in the overall design.’

Opposite the prophets are the kneeling martyrs, each with a yellow halo. From the viewer’s left to right are:

- St Stephen in a white alb and yellow-bordered blue dalmatic, with a yellow-fringed maniple over his left arm. His head is tonsured and there are three stones on the hem of his dalmatic.

- St George dressed in armour over which is a white tabard with a red cross.

- St Clement, with a bishop’s mitre, in a light-maroon coat with an apparel of the amice. Part of his attribute, an anchor, can be seen.

- A largely obscured figure with a tonsured head and a white robe.

- St Catherine of Alexandria wearing a coronet over a white veil and a purple gown, with her wheel beside her.

- St Edmund in a blue robe and white ermine-bordered cloak, with a red arrow leaning against his left shoulder.

- St Alban dressed in armour. Worn over it is a blue tunic with a yellow saltire cross. He also wears a red-lined white cloak.

- St Alphage in a yellow-lined white cope embroidered with black lozenges bearing the yellow capital letter A. The cope is fastened with an oval white morse. He is wearing a white and gold mitre.

- St Faith wearing a coronet over a white veil, and a green gown with a rope wound around her waist.

At the foot of the central light is a scrolled cartouche with text on a multi-coloured background. Behind the cartouche and stretching across all five lights is a panorama of churches and cathedrals – THE HOLY CHURCH THROUGHOUT ALL THE WORLD – against a blue sky and green hills. Travers mentions that these buildings include the Duomo, Florence; Notre Dame, Paris; Canterbury Cathedral; and St Paul’s, London. These remain the only buildings identified to date. In a white rectangle to the left of St Paul’s is the inscription: GIVEN FOR THE ADORNMENT OF GOD’S HOUSE BY A MEMBER OF THIS CONGREGATION ANNO D-M-NI 1936.

In 1998 art historian Peter Cormack visited St George’s and drew attention to the significance of the work by Travers and Crawford. Following the visit he wrote that ‘unlike Comper – the other well-known luminary in the field and under whom Travers trained for a while – Travers was committed to an original and modern interpretation of diverse stylistic traditions’. The window ‘is in his characteristic style of the 1930s, which blends elements derived from late 15th-century English/French stained glass with an attractively contemporary style of drawing. As always with Travers’ work, the lettering is beautifully designed and plays an important part in the overall design.’

Pulpit by Martin Travers

Pulpit by Martin Travers

New furnishings by Travers and Crawford

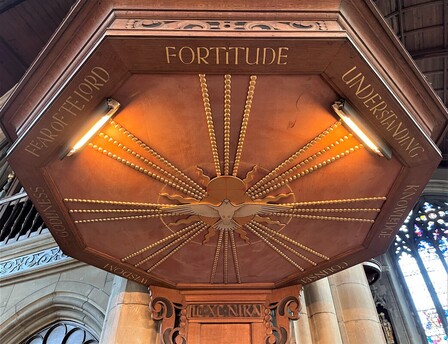

In April 1939 it was reported to the PCC that the Mothers’ Union had begun collecting to provide a new pulpit. By February 1940 Martin Travers had visited to take measurements and promised to submit a design and estimate at the earliest opportunity. Travers met with the PCC in May 1940 when his neo Jacobean design for construction in oak was agreed. The final cost was £185. It is the only Travers pulpit complete with tester. The Parish Magazine described the dedication, which took place on 16th November 1941, as ‘a very bright and notable event in the history of St George’s’, and said

the pulpit has certainly improved the acoustic properties of the church very much and, thanks to the genius of Mr Martin Travers, it is in beautiful harmony with all the surroundings. Its decoration should be a lasting inspiration. The underside of the sounding board bears a carved representation of the Holy Dove, surrounded by the names of the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit. On the panel at the back is the Greek inscription ‘IC XC NIKA’, meaning ‘Jesus Christ conquers’. On the front panel is the gilded sacred monogram ‘IHS’, ‘Jesus our Saviour’.

The Second World War memorial at St George’s was a godsend rather than another reward of discerning patronage. The PCC had decided to commission an oak high altar reredos and, without consulting the Diocese of London, had approved a design by one of its own members, an architectural draughtsman. Fundraising began, including door-to-door leafleting, but when in early 1947 the design was forwarded to the DAC it was unimpressed and suggested that ‘something entirely fresh and more harmonious with the church’s architecture should be devised’. New Vicar George Appleton, lately Archdeacon of Rangoon, later Archbishop in Jerusalem, asked if the DAC could send someone along to discuss the matter. The emissary was Judith Scott, then assistant to Dr Francis Eeles, Secretary to the Central Council for the Care of Churches.

A few months before, John Betjeman, researching his Collins Guide to English Parish Churches, had met Judith Scott at Francis Eeles’s house. He wrote to him afterwards, thanking him for his help and proposing next time to ‘take Miss Scott to the cinema so that she will be able to clear some of those rood lofts out of her mind’. She and Betjeman became great friends. She later succeeded Francis Eeles as Secretary to the Central Council and was, in the words of architectural historian Peter Burman, ‘elegant, upright and true’.

In her report following her visit to St George’s Judith Scott said that she was ‘impressed with the dignity and fine proportions of the church’ and was ‘inclined to think that it is the best thing that the architect has ever built. The architectural detail is in the true line of the Gothic tradition: he has used massive timbers and the best materials obtainable, and used them with great skill and a certain subtlety’. She thought it promised, when complete, to be one of the best early twentieth-century churches in the diocese. On the thorny issue of the reredos, she recommended that Martin Travers or one of his old pupils be called in to prepare a new design.

In April 1939 it was reported to the PCC that the Mothers’ Union had begun collecting to provide a new pulpit. By February 1940 Martin Travers had visited to take measurements and promised to submit a design and estimate at the earliest opportunity. Travers met with the PCC in May 1940 when his neo Jacobean design for construction in oak was agreed. The final cost was £185. It is the only Travers pulpit complete with tester. The Parish Magazine described the dedication, which took place on 16th November 1941, as ‘a very bright and notable event in the history of St George’s’, and said

the pulpit has certainly improved the acoustic properties of the church very much and, thanks to the genius of Mr Martin Travers, it is in beautiful harmony with all the surroundings. Its decoration should be a lasting inspiration. The underside of the sounding board bears a carved representation of the Holy Dove, surrounded by the names of the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit. On the panel at the back is the Greek inscription ‘IC XC NIKA’, meaning ‘Jesus Christ conquers’. On the front panel is the gilded sacred monogram ‘IHS’, ‘Jesus our Saviour’.

The Second World War memorial at St George’s was a godsend rather than another reward of discerning patronage. The PCC had decided to commission an oak high altar reredos and, without consulting the Diocese of London, had approved a design by one of its own members, an architectural draughtsman. Fundraising began, including door-to-door leafleting, but when in early 1947 the design was forwarded to the DAC it was unimpressed and suggested that ‘something entirely fresh and more harmonious with the church’s architecture should be devised’. New Vicar George Appleton, lately Archdeacon of Rangoon, later Archbishop in Jerusalem, asked if the DAC could send someone along to discuss the matter. The emissary was Judith Scott, then assistant to Dr Francis Eeles, Secretary to the Central Council for the Care of Churches.

A few months before, John Betjeman, researching his Collins Guide to English Parish Churches, had met Judith Scott at Francis Eeles’s house. He wrote to him afterwards, thanking him for his help and proposing next time to ‘take Miss Scott to the cinema so that she will be able to clear some of those rood lofts out of her mind’. She and Betjeman became great friends. She later succeeded Francis Eeles as Secretary to the Central Council and was, in the words of architectural historian Peter Burman, ‘elegant, upright and true’.

In her report following her visit to St George’s Judith Scott said that she was ‘impressed with the dignity and fine proportions of the church’ and was ‘inclined to think that it is the best thing that the architect has ever built. The architectural detail is in the true line of the Gothic tradition: he has used massive timbers and the best materials obtainable, and used them with great skill and a certain subtlety’. She thought it promised, when complete, to be one of the best early twentieth-century churches in the diocese. On the thorny issue of the reredos, she recommended that Martin Travers or one of his old pupils be called in to prepare a new design.

Soffit of pulpit tester by Martin Travers

Soffit of pulpit tester by Martin Travers

Faced with further PCC wrangling the DAC stood firm ‘in view especially of the importance and beauty of the church generally and in particular of the existence above the altar of the window by Mr Martin Travers’. Echoing the advice of Judith Scott, the Committee considered that ‘by far the best course would be to seek the advice and, if possible, the services of Mr Travers’.

In September 1947 St George’s PCC was informed of ‘certain difficulties’ in engaging Travers. Francis Stephens, Travers’ pupil at the RCA, wrote of him being inundated with work around this time with a large backlog of uncompleted contracts and chaotic correspondence. Stephens helped to sort out the letters after Travers’ unexpected death from a heart attack on 25th July 1948 and gives an example of a typical series:

‘Dear Mr T, We are all so pleased that you were able to visit St XYZ and discuss the proposed scheme/statue/altar/window. We look forward to your designs and estimates etc, etc.’

Next would be, ‘Dear Mr T, We have not heard from you about the drawings as yet; can you send them soon as our donor is anxious to go ahead …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Our people are getting rather impatient, please …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Can we please have some idea of when …’ ‘Dear Mr T, We have your designs and they are magnificent. Can you please let us have some idea of costs and time …’ ‘Dear Mr T, We have heard nothing from you now for x weeks (months!) …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Can we please have your approximate costs and some idea of time …’ ‘Mr T, We regret that if we cannot have some further information we shall …’ ‘Mr T, Please will you …’

Correspondingly there would be others on the lines of ‘When can we expect the stained glass … carving … panel promised for … the Bishop is booked … the donor is anxious … etc, etc.’

On the other hand of course, everything was marvellous when the work actually did appear!

In September 1947 St George’s PCC was informed of ‘certain difficulties’ in engaging Travers. Francis Stephens, Travers’ pupil at the RCA, wrote of him being inundated with work around this time with a large backlog of uncompleted contracts and chaotic correspondence. Stephens helped to sort out the letters after Travers’ unexpected death from a heart attack on 25th July 1948 and gives an example of a typical series:

‘Dear Mr T, We are all so pleased that you were able to visit St XYZ and discuss the proposed scheme/statue/altar/window. We look forward to your designs and estimates etc, etc.’

Next would be, ‘Dear Mr T, We have not heard from you about the drawings as yet; can you send them soon as our donor is anxious to go ahead …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Our people are getting rather impatient, please …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Can we please have some idea of when …’ ‘Dear Mr T, We have your designs and they are magnificent. Can you please let us have some idea of costs and time …’ ‘Dear Mr T, We have heard nothing from you now for x weeks (months!) …’ ‘Dear Mr T, Can we please have your approximate costs and some idea of time …’ ‘Mr T, We regret that if we cannot have some further information we shall …’ ‘Mr T, Please will you …’

Correspondingly there would be others on the lines of ‘When can we expect the stained glass … carving … panel promised for … the Bishop is booked … the donor is anxious … etc, etc.’

On the other hand of course, everything was marvellous when the work actually did appear!

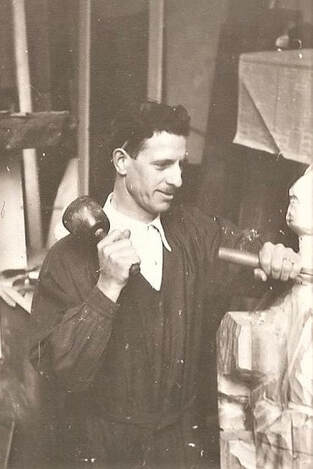

John Crawford

John Crawford

In the circumstances, it was proposed and agreed that St George’s PCC ask Faith Craft – the Society of the Faith’s church furnishing studio –to submit a design in consultation with Martin Travers’ chief assistant, John Crawford. Quite when the relationship between the Martin Travers studio and Faith Craft began is uncertain, but there is evidence that Travers subcontracted joinery and wood-turning to the firm during the Second World War.

It is likely that Martin Travers met John Crawford at the Glass House premises of Lowndes and Drury. Travers rented a studio at the Glass House from around 1918 until 1926; Lowndes & Drury continued to cut, fire, glaze, and fix his windows after he established his own studio. Crawford was employed by Lowndes and Drury on a freelance basis between 1920 and 1926. In 1925 Travers was appointed chief instructor in stained glass at the RCA. Crawford appears in the College’s earliest surviving prospectus, 1926-27, as the technical instructor in stained glass; a position he held until 1959.

Crawford’s versatility must have owed much to his early training. Aged fourteen he was apprenticed to London-based artist-craftsman John H M Bonnor: a stained glass artist, sculptor, metalworker, and designer and maker of jewellery. John Crawford was Martin Travers’ chief assistant from 1924 until 1948; as well as working in stained glass he was Travers’ sculptor and carver, senior decorator, and on occasion deputed designer.

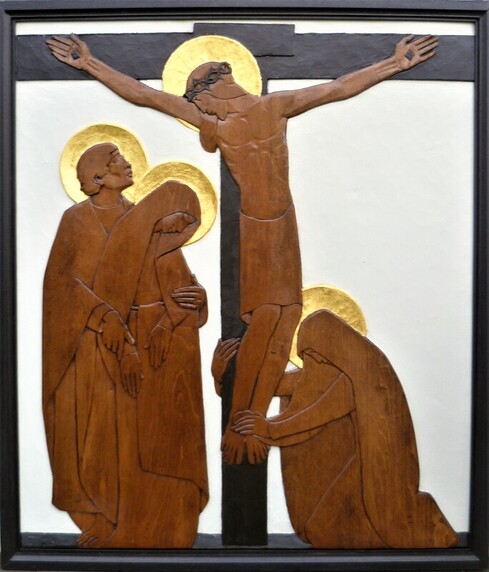

It was reported in the Parish Magazine that John Crawford had taken a large part in the work on the east window. His Second World War memorial beneath it comprises an oak triptych reredos flanked by a carved relief of St George and the dragon and a stone memorial tablet. The reredos doors contain a Fra Angelico-inspired Annunciation similar to the depictions of the archangel Gabriel and Our Lady in the smaller triptychs at St Mary’s, Ticehurst, and St Mary’s, Sixpenny Handley, designed by Travers in 1945.

It is likely that Martin Travers met John Crawford at the Glass House premises of Lowndes and Drury. Travers rented a studio at the Glass House from around 1918 until 1926; Lowndes & Drury continued to cut, fire, glaze, and fix his windows after he established his own studio. Crawford was employed by Lowndes and Drury on a freelance basis between 1920 and 1926. In 1925 Travers was appointed chief instructor in stained glass at the RCA. Crawford appears in the College’s earliest surviving prospectus, 1926-27, as the technical instructor in stained glass; a position he held until 1959.

Crawford’s versatility must have owed much to his early training. Aged fourteen he was apprenticed to London-based artist-craftsman John H M Bonnor: a stained glass artist, sculptor, metalworker, and designer and maker of jewellery. John Crawford was Martin Travers’ chief assistant from 1924 until 1948; as well as working in stained glass he was Travers’ sculptor and carver, senior decorator, and on occasion deputed designer.

It was reported in the Parish Magazine that John Crawford had taken a large part in the work on the east window. His Second World War memorial beneath it comprises an oak triptych reredos flanked by a carved relief of St George and the dragon and a stone memorial tablet. The reredos doors contain a Fra Angelico-inspired Annunciation similar to the depictions of the archangel Gabriel and Our Lady in the smaller triptychs at St Mary’s, Ticehurst, and St Mary’s, Sixpenny Handley, designed by Travers in 1945.

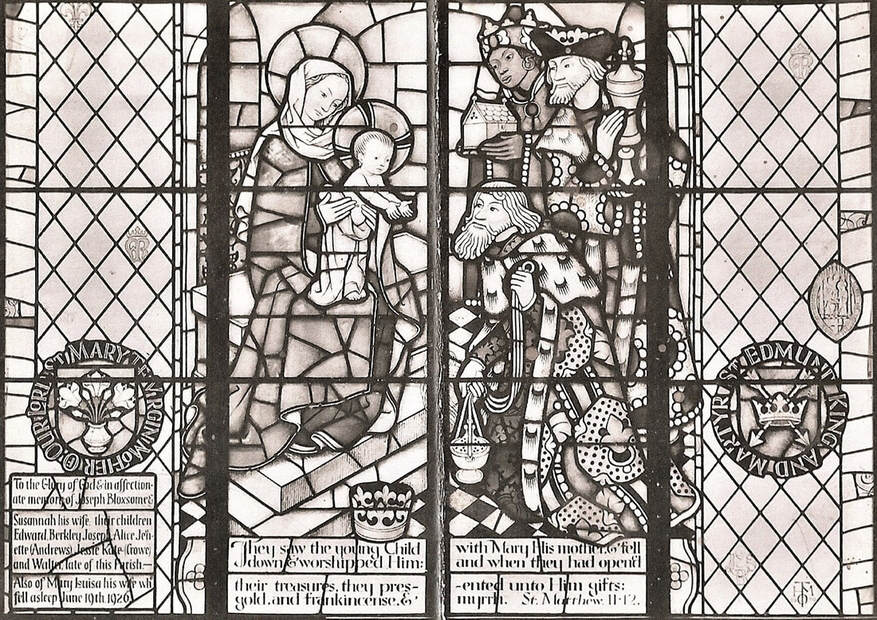

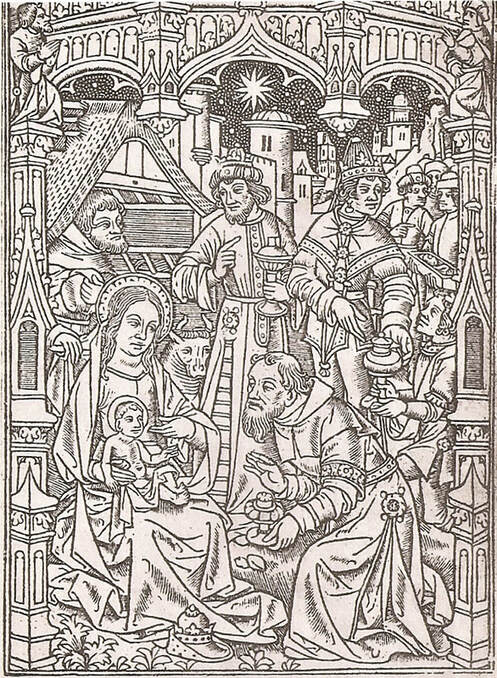

Crawford’s Adoration of the Magi design for the central panel is dated 28th November 1947. It is influenced by Travers’ 1940 east window at St Mary’s, Woodbridge, which was inspired by a relief print by Thielman Kerver from 1500. A reproduction of the Kerver print on card is in the Crawford archive, included in one of Travers’ scrap books of images of architectural and artistic works. Crawford retains Travers features in the Woodbridge window such as the Virgin’s posture, the Christ Child’s outstretched arms, the tiled floor, African magus, and fur-trimmed cloak and fur hood on one of his magi. In other details Crawford follows Kerver: the inclusion of St Joseph, the star, the kneeling magus on the same level as the Virgin and Child, his robes, the footed, lidded vessel he is holding, and the position of his hands.

Lady Chapel screens by John Crawford

Lady Chapel screens by John Crawford

Although the design of the reredos is in the Travers style, the deep texturing of the robes of the figures in the central panel is not characteristic of carved work signed-off by Martin Travers. No other Faith Craft piece of the time shows the same carving or colouring techniques. Writing to Francis Eeles in July 1948 Faith Craft’s manager George Beadle says that he has Crawford in mind as sculptor for projected work at St Gregory’s, Horfield, Bristol, and that ‘he is doing quite a lot of work for us’. It would appear therefore that, relishing the latitude to further demonstrate his skills, John Crawford himself carved and decorated the figures on the reredos. It is very likely that he also carved and decorated the relief of St George and the dragon and engraved and coloured the lettering on the memorial tablet. A late Arts & Crafts tour de force, the Second World War memorial was dedicated on 26th June 1949.

The Lady Chapel oak screens, designed by Crawford in January 1948 and made by Faith Craft, were dedicated on Christmas morning 1949. They were commissioned as a memorial to long-standing member and former churchwarden T Vincent Howells. Also in the Travers idiom, the combination of arcading and turnings on the upper part of the screens resembles the backs of so-called ‘Derbyshire’ chairs of the Restoration era. The cost of the screens was £750, just twenty pounds less than the Second World War memorial.

John Crawford maintained a freelance relationship with Faith Craft as a designer and technical specialist and engaged the firm in the completion of Travers’ outstanding work as well as his own projects.

The Lady Chapel oak screens, designed by Crawford in January 1948 and made by Faith Craft, were dedicated on Christmas morning 1949. They were commissioned as a memorial to long-standing member and former churchwarden T Vincent Howells. Also in the Travers idiom, the combination of arcading and turnings on the upper part of the screens resembles the backs of so-called ‘Derbyshire’ chairs of the Restoration era. The cost of the screens was £750, just twenty pounds less than the Second World War memorial.

John Crawford maintained a freelance relationship with Faith Craft as a designer and technical specialist and engaged the firm in the completion of Travers’ outstanding work as well as his own projects.

Lady Chapel reredos and candlesticks by Martin Travers

Lady Chapel reredos and candlesticks by Martin Travers

Renewed interest

In 1997 the Ecclesiological Society published a booklet on Martin Travers which included Crawford’s 1965 article ‘The Travers School of Glass’ and Francis Stephens' reminiscences. Michael Yelton has since brought out two books on Martin Travers: the first, together with Rodney Warrener, in 2003, and a larger and more lavishly illustrated volume in 2016. In 2015 the Society of the Faith published All Manner of Workmanship, drawing on papers delivered at a symposium on Faith Craft held at St George’s, Headstone in 2013.

Between Peter Cormack’s visit in 1998 and the Faith Craft symposium there were several additions to the St George’s Travers-Crawford ensemble.

The Lady Chapel reredos, from St Stephen’s, Battersea, and the west wall Holy Dove, part of a reredos from St James’s, Watford, are both by Martin Travers. They were donated to St George’s in 1999 by Mr W Peter Anelay. Tassels and cartouches from the Watford altarpiece were used in the Alpha and Omega high altar reredos scheme, visible when the doors are closed during Advent and Lent.

The Martin Travers high altar crucifix and Lady Chapel candlesticks, originally in St Peter’s, Limehouse, were acquired in 2013.

In 1997 the Ecclesiological Society published a booklet on Martin Travers which included Crawford’s 1965 article ‘The Travers School of Glass’ and Francis Stephens' reminiscences. Michael Yelton has since brought out two books on Martin Travers: the first, together with Rodney Warrener, in 2003, and a larger and more lavishly illustrated volume in 2016. In 2015 the Society of the Faith published All Manner of Workmanship, drawing on papers delivered at a symposium on Faith Craft held at St George’s, Headstone in 2013.

Between Peter Cormack’s visit in 1998 and the Faith Craft symposium there were several additions to the St George’s Travers-Crawford ensemble.

The Lady Chapel reredos, from St Stephen’s, Battersea, and the west wall Holy Dove, part of a reredos from St James’s, Watford, are both by Martin Travers. They were donated to St George’s in 1999 by Mr W Peter Anelay. Tassels and cartouches from the Watford altarpiece were used in the Alpha and Omega high altar reredos scheme, visible when the doors are closed during Advent and Lent.

The Martin Travers high altar crucifix and Lady Chapel candlesticks, originally in St Peter’s, Limehouse, were acquired in 2013.

John Crawford font cover with Martin Travers soffit and west wall

Holy Dove

John Crawford font cover with Martin Travers soffit and west wall

Holy Dove

The last Faith Craft design put into production was the St George’s font cover, designed by John Crawford for the church in February 1948 but with George Appleton then unable to find a donor. Made by former Faith Craft sculptor and decorator Siegfried Pietzsch together with joiner John Warner, it was dedicated in 2003. The cover incorporates the soffit from the Martin Travers font cover from St Stephen’s, Battersea, also donated by W Peter Anelay. The supporting pillars and arcading under the soffit resemble Travers’ design for the font cover at St Swithun, Compton Beauchamp, installed around 1934.

Very little about John Crawford was known until in 2013 his archive, including Martin Travers material, was found to be with his grandson Michael Crawford. It is now with the RIBA, together with the Travers archive. In addition to suitcases, boxes, and bags of photographs, drawings, and papers was a life-size statue of the Virgin and Child. There was an accompanying note John Crawford had written in 1975 stating that the original, which he had carved for Travers in pine, was in St Andrew’s, Catford. He says that three plaster castings were made from the statue, the first two having gone to St John’s, Upper Norwood, and St John the Baptist Convent Church, Clewer. Travers’ trustees agreed to sell him the third casting along with other items he had made. At the time the note was written Crawford was aged 78 and his memory not entirely accurate: a fourth plaster version of the Virgin and Child statue was supplied to St Thomas’s, Oxford. There is no known record of the original carved statue having been at St Andrew’s, Catford. Whether or not from there, it eventually found its way to St John’s, Timberhill, Norwich.

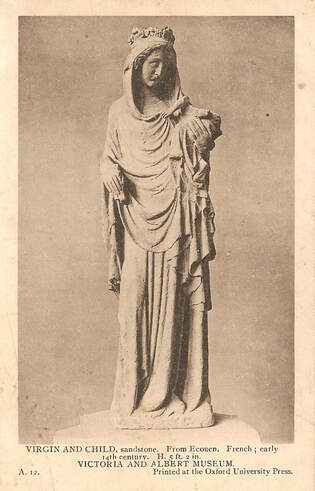

Dating from around 1920, ‘Our Lady Queen of Peace’ in St Mary’s, Bourne Street, Pimlico bears a close similarity to the Virgin and Child carved by Crawford; in fact the posture is identical. Travers’ inspiration for the Bourne Street statue had been a subject of speculation until the discovery in the Crawford archive of a photograph printed on card showing an early fourteenth-century stone statue from Ecouen, near Paris, at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Very little about John Crawford was known until in 2013 his archive, including Martin Travers material, was found to be with his grandson Michael Crawford. It is now with the RIBA, together with the Travers archive. In addition to suitcases, boxes, and bags of photographs, drawings, and papers was a life-size statue of the Virgin and Child. There was an accompanying note John Crawford had written in 1975 stating that the original, which he had carved for Travers in pine, was in St Andrew’s, Catford. He says that three plaster castings were made from the statue, the first two having gone to St John’s, Upper Norwood, and St John the Baptist Convent Church, Clewer. Travers’ trustees agreed to sell him the third casting along with other items he had made. At the time the note was written Crawford was aged 78 and his memory not entirely accurate: a fourth plaster version of the Virgin and Child statue was supplied to St Thomas’s, Oxford. There is no known record of the original carved statue having been at St Andrew’s, Catford. Whether or not from there, it eventually found its way to St John’s, Timberhill, Norwich.

Dating from around 1920, ‘Our Lady Queen of Peace’ in St Mary’s, Bourne Street, Pimlico bears a close similarity to the Virgin and Child carved by Crawford; in fact the posture is identical. Travers’ inspiration for the Bourne Street statue had been a subject of speculation until the discovery in the Crawford archive of a photograph printed on card showing an early fourteenth-century stone statue from Ecouen, near Paris, at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Plaster Virgin and Child by Martin Travers, St George’s, Headstone

Plaster Virgin and Child by Martin Travers, St George’s, Headstone

One claim for the Bourne Street statue was that Travers’ wild, promiscuous wife Christine may have modelled for it. As the drapery is closely copied from the statue in the V&A that seems highly unlikely. Furthermore, a comparison of the face of ‘Our Lady Queen of Peace’ with Travers’ sketch of Christine shows little resemblance. There is a closer likeness, however, to the face in the Crawford carving and castings. Christine Travers died in 1934; the design for the Upper Norwood statue, probably the earliest of the plaster castings taken from the Crawford-carved statue to leave the studio, is dated 1935. This raises the question whether, around the time of her death and unknown to his clients, Travers memorialised the colourful Christine as the Blessed Virgin. Michael Crawford donated his statue to St George’s, Headstone and it made its appearance in church on eve of the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 2013. As with the plaster casting at St Thomas’s, Oxford, but unlike those at Upper Norwood and Clewer, it retains its fixed crown. In Martin Travers’ studio at the time of his death, the statue is now enclosed and dignified by the screens providentially designed for it by John Crawford and made by Faith Craft.

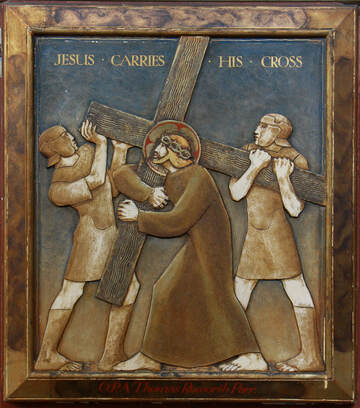

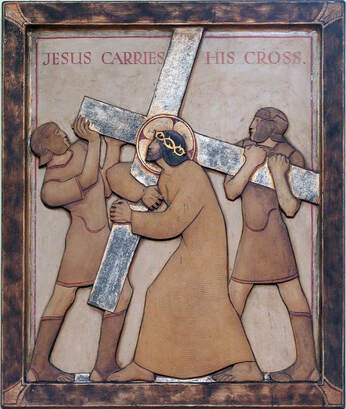

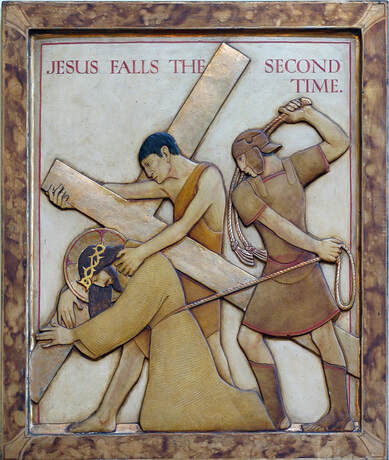

The Faith Craft symposium came about through interest generated by the church’s acquisition of an early 1930s set of Stations of the Cross designed by Ian Howgate and carved by William Wheeler. It must be among the earliest produced by an Anglican furnishing studio for Anglican devotional use. In the course of researching All Manner of Workmanship, however, an earlier set was discovered. For many years these Stations were stored in the garage loft of former Faith Craft craftsman Michael Carter, who was given them when the firm’s Abbey Mill studio in St Albans closed in 1969. Not the work of Faith Craft, the wooden panels are the original Travers studio carvings from which the much-admired plaster sets at St Augustine’s, Queen’s Gate, South Kensington, and Holy Redeemer, Clerkenwell were made. The Queen’s Gate set was installed around 1928 and the Clerkenwell set in 1931.

The Faith Craft symposium came about through interest generated by the church’s acquisition of an early 1930s set of Stations of the Cross designed by Ian Howgate and carved by William Wheeler. It must be among the earliest produced by an Anglican furnishing studio for Anglican devotional use. In the course of researching All Manner of Workmanship, however, an earlier set was discovered. For many years these Stations were stored in the garage loft of former Faith Craft craftsman Michael Carter, who was given them when the firm’s Abbey Mill studio in St Albans closed in 1969. Not the work of Faith Craft, the wooden panels are the original Travers studio carvings from which the much-admired plaster sets at St Augustine’s, Queen’s Gate, South Kensington, and Holy Redeemer, Clerkenwell were made. The Queen’s Gate set was installed around 1928 and the Clerkenwell set in 1931.

The location of these panels at the Abbey Mill studio suggests that after Travers’ death Crawford offered them to Faith Craft for the production of further sets, but there is no evidence that any more were made. That John Crawford designed as well as carved the panels is indicated by his own framed photos of the Clerkenwell set, complete with his name and the address of Travers’ studio in Colet Gardens, West Kensington. The Crawford archive includes signed pen and ink drawings of seven of the designs dated 1940, perhaps intended for printing.

The figures in the Crawford Stations are close in style to those in the 1922 Travers window in St Gabriel’s, Cricklewood; the same figures of Christ and Simon Cyrene in the central light are inverted in Station 7, ‘Jesus Falls the Second Time’.

As it was never intended that these carvings would be displayed it was of no concern that the boards used to form the panels were of uneven colour or irregular grain. The panels were acquired by St George's in 2015 and, like the Virgin and Child statue, cleaned and decorated by fine art restorer John Malcolm. They were dedicated in 2018.

In an article entitled ‘Slow Art', Bishop Robert Ladds observes that 'we shall find high art only rarely in the illustrations that accompany the Stations of the Cross’. Those he recognises as 'captivating and remarkable works of art' are the stone sets by Eric Gill at Westminster Cathedral and St Cuthbert's, Bradford, and the wooden set by John Crawford at St George's, Headstone.

Peter Cormack writes of Martin Travers as one of the most influential stained glass designers of the twentieth century and Alan Brooks says that his Te Deum at St George’s is his most significant window of the period. This important work, harmoniously complemented by distinguished furnishings by Crawford and Travers himself, is the major highlight of the building’s splendid interior.

In 1950 George Appleton stated ‘we have one of the most beautiful and worshipful of all the churches that have been built this century: let us pray and worship all the more faithfully and sincerely’. The challenge resonates even more strongly in the completed, fully-appointed St George’s, Headstone.

Stephen Keeble

2021

In an article entitled ‘Slow Art', Bishop Robert Ladds observes that 'we shall find high art only rarely in the illustrations that accompany the Stations of the Cross’. Those he recognises as 'captivating and remarkable works of art' are the stone sets by Eric Gill at Westminster Cathedral and St Cuthbert's, Bradford, and the wooden set by John Crawford at St George's, Headstone.

Peter Cormack writes of Martin Travers as one of the most influential stained glass designers of the twentieth century and Alan Brooks says that his Te Deum at St George’s is his most significant window of the period. This important work, harmoniously complemented by distinguished furnishings by Crawford and Travers himself, is the major highlight of the building’s splendid interior.

In 1950 George Appleton stated ‘we have one of the most beautiful and worshipful of all the churches that have been built this century: let us pray and worship all the more faithfully and sincerely’. The challenge resonates even more strongly in the completed, fully-appointed St George’s, Headstone.

Stephen Keeble

2021

Bibliography

Peter E Blagdon-Gameln (ed), Martin Travers 1886-1948: A Handlist of his Work, Ecclesiological Society, 1997.

Alan Brooks, The Stained Glass of Francis Spear, privately published, 2012.

Sandra Coley (ed), The Journal of Stained Glass, ‘The Glass House Special Edition’, vol XLI, BSMGP, London, 2017.

Peter Cormack, 'Stained-Glass Windows in St George's Church, Headstone', letter to Stephen Keeble, 17th July 1998.

John Hayward, ‘Martin Travers (1886-1948)’ in Church Building, issue 84, November/December 2003, pp52-54, Gabriel Communications, Manchester.

Stephen Keeble, ‘Faith Craft and St George’s, Headstone’ in All Manner of Workmanship, pp85-115, Robert Gage (ed), Spire Books, Salisbury, 2015.

Robert Ladds, ‘Slow Art’ in New Directions, October 2019, p12, Forward in Faith, London.

Rodney Warrener and Michael Yelton, Martin Travers 1886-1948: an Appreciation, Unicorn Press, London, 2003.

Michael Yelton, Martin Travers: His Life and Work, Spire Books, Salisbury, 2016

Peter E Blagdon-Gameln (ed), Martin Travers 1886-1948: A Handlist of his Work, Ecclesiological Society, 1997.

Alan Brooks, The Stained Glass of Francis Spear, privately published, 2012.

Sandra Coley (ed), The Journal of Stained Glass, ‘The Glass House Special Edition’, vol XLI, BSMGP, London, 2017.

Peter Cormack, 'Stained-Glass Windows in St George's Church, Headstone', letter to Stephen Keeble, 17th July 1998.

John Hayward, ‘Martin Travers (1886-1948)’ in Church Building, issue 84, November/December 2003, pp52-54, Gabriel Communications, Manchester.

Stephen Keeble, ‘Faith Craft and St George’s, Headstone’ in All Manner of Workmanship, pp85-115, Robert Gage (ed), Spire Books, Salisbury, 2015.

Robert Ladds, ‘Slow Art’ in New Directions, October 2019, p12, Forward in Faith, London.

Rodney Warrener and Michael Yelton, Martin Travers 1886-1948: an Appreciation, Unicorn Press, London, 2003.

Michael Yelton, Martin Travers: His Life and Work, Spire Books, Salisbury, 2016